In 1959, Fidel Castro entered Havana to cheers, promising freedom, land reform, and justice. Within a year, he had seized private property, shut down the free press, and jailed political opponents. Churches were closed or tightly controlled. By 1965, Cuba had become a Soviet-aligned state with no free elections, no independent courts, and no religious freedom. Yet even as thousands of Cubans fled repression, Castro was praised by some on the American left who viewed him as a symbol of anti-imperialism and economic justice.

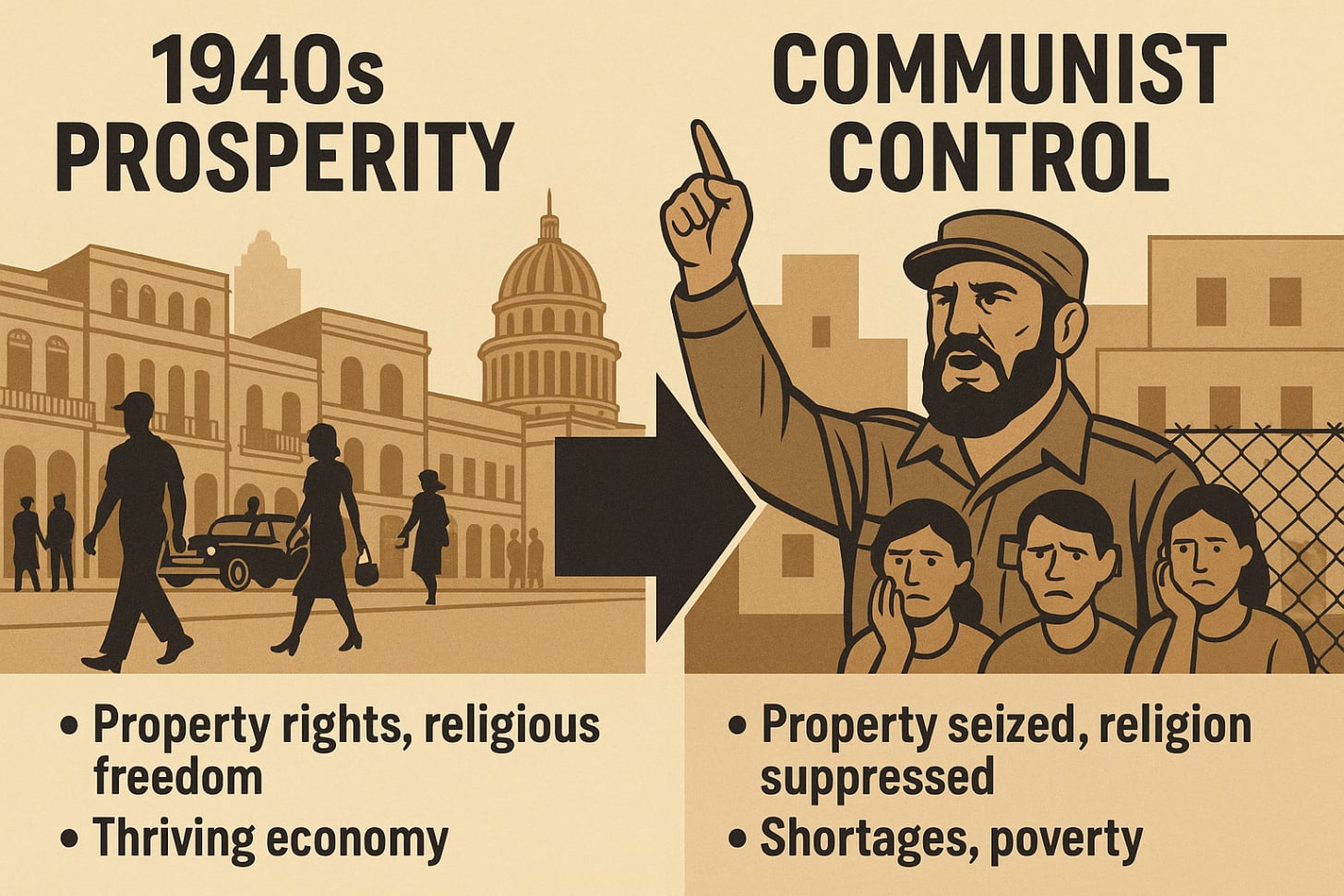

In the 1940s and early 1950s, Cuba’s economy ranked among the highest in Latin America. It had a written constitution, an elected legislature, and independent civil institutions. But economic inequality, rural poverty, and Batista’s 1952 coup eroded public trust in the system. Castro capitalized on this discontent with a populist message that promised moral reform and national dignity.

Once in power, his regime moved fast. Between 1960 and 1961, the government nationalized U.S. businesses, confiscated Cuban-owned homes and farms, and removed judges who opposed the new order. In 1961, private schools were closed and over 130 priests expelled. Religious leaders were barred from political life. Surveillance became routine, executions common,

and neighborhood watch groups encouraged citizens to report on each other.

Support from parts of the U.S. left grew during this period. Writers, academics, and political organizations praised Cuba’s expansion of education and healthcare. Some compared its social programs to movements for civil rights and equality. Public statements and published essays framed the Cuban model as a break from imperial control and capitalism. Criticism of one-party rule or religious repression was often dismissed as Cold War propaganda or deflected as the price of resisting U.S. influence.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Cuba positioned itself as a beacon for anti-colonial and revolutionary movements. The island hosted conferences and training for activists across Latin America and Africa. U.S.-based solidarity groups echoed Cuban rhetoric about liberation and equality. In many circles, the regime’s treatment of dissidents and religious groups was downplayed or ignored.

The consequences of that support

While some support came from genuine belief in Cuba’s revolutionary ideals, others failed to engage critically with the regime’s authoritarian nature. Cuban exiles, political prisoners, and religious dissidents shared detailed accounts of repression, but these were often disregarded or sidelined in sympathetic circles. As a result, the Cuban government received decades of political cover, even as it carried out widespread human rights violations.

Meanwhile, inside Cuba, the consequences of centralization deepened. Citizens who expressed opposition lost access to jobs, housing, or exit permits. Churches operated under licenses and were regularly monitored. Political prisoners, including pastors and lay leaders, served long sentences for holding unauthorized meetings or owning unregistered religious materials.

Life today

The Cuban government still controls most of the economy, including media, healthcare, and education. Wages are extremely low, averaging less than $30 USD per month. Families rely heavily on ration cards, remittances from abroad, or black-market trade. Shortages of fuel, electricity, and medicine are routine. Travel restrictions remain in place, and access to independent media is limited.

Religious institutions face legal and bureaucratic pressure. While the constitution no longer declares Cuba an atheist state, it places religion under regulation. Churches must register with the Office of Religious Affairs. Unauthorized house churches may be fined or shut down. Clergy who challenge government policy risk surveillance or arrest.

The 2021 protests over economic conditions and political repression brought thousands to the streets. Dozens of pastors and religious leaders were detained. Internet access was cut. Trials were swift and punitive. The government reaffirmed its commitment to one-party rule and labeled dissent as a threat to the revolution.

A cautionary tale

Cuba’s transformation illustrates how revolutionary ideals can be used to justify permanent restrictions on liberty. Castro promised social reform, but replaced one authoritarian regime with another. The constitution now protects the revolution itself, not the rights of individuals. Dissent is framed as betrayal. Courts enforce political loyalty, not legal fairness.

Sympathy from foreign observers helped shield the regime from international accountability. The idealized image of Cuba as a champion of equality often ignored or minimized the daily reality of repression. The result was a one-sided narrative that disregarded religious persecution, state control of life, and the long-term loss of freedom.

Cuba’s experience stands as a warning about the risks of consolidating power without limits. When courts, the press, and religious groups lose independence, there are few ways left for a society to correct course.

Cuba’s constitution prioritizes political ideology over individual rights. The Communist Party is defined as the supreme force in society. Citizens have no legal mechanism to challenge the state’s authority. Courts are not independent. Political speech, private enterprise, and religious activity all operate under state regulation or permission.

The state’s control of religious institutions prevents churches from functioning as centers of independent thought. Licensing requirements and administrative restrictions allow the government to shut down or limit religious groups at will. Leaders who speak critically of the regime face surveillance, detention, or travel bans.

The Cuban legal model is built to preserve the revolution rather than protect liberties. Unless the constitutional framework changes, reforms will remain tightly controlled and reversible. Civil and religious freedoms continue to exist only within state-defined limits.

Like this article? Subscribe and share

If you found this reporting helpful, please share it and subscribe to ReligiousLiberty.TV at religiouslibertytv.substack.com. Get early access to new stories, expert legal analysis, and case alerts on religious liberty and civil rights around the world.

TLDR (Too Long / Didn’t Read Summary)

Cuba shifted from a constitutional republic to a one-party socialist state after Fidel Castro took power in 1959. The regime nationalized property, eliminated opposition, and restricted religious freedom. Many Cubans supported the revolution early, while others stayed silent out of fear. Some U.S. left-wing voices praised the regime’s social programs while overlooking repression. Today, Cuba remains under one-party rule, with widespread shortages and limited personal freedoms. The story offers a warning about unchecked power and ideology.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For personal legal questions, consult a licensed attorney.

AI Disclaimer: This article was AI-assisted. All quotations and facts have been independently verified.

SEO Tags: Cuba socialism history, religious freedom Cuba, Castro government repression, American support for Cuba, Cuba property rights erosion

Source: ReligiousLibertyTV on Substack