[dc]H[/dc]ave you ever wondered what legal mechanism existed that permitted the legalization of slavery in the United States after the Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791? How it was that men, women, and children were held in bondage after Francis Scott Key wrote the famous words, “land of the free, and the home of the brave” in 1812? How segregation persisted in law until the late 1960s?

When the United States was formed, a nearly fatal flaw was baked into the founding documents. Before the new nation was developed as a federation of states, the southern colonies were unwilling to join the new nation because they felt that slavery was essential to their economy and way of life. They refused to join the United States if it would outlaw slavery.

While the founders of this nation were in many ways visionaries, and many had grave reservations about admitting slave states, some owned slaves themselves and others were satisfied to put their convictions aside to be dealt with by future generations. They were not willing to give up on the new republic because of the issue of slavery.

But the fact that this injustice was allowed to fester throughout the first decades would lead to incredible destruction just a few generations later.

[perfectpullquote align=”left” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Before the Civil War, in order to protect slavery, the Bill of Rights only applied to actions of the Federal government. It did not apply at the state level.[/perfectpullquote]

Legally, in order to protect the “peculiar institution” of slavery, the Bill of Rights, or the first ten amendments to the Constitution, including the First Amendment with its protections of free speech, free exercise of religion, and the establishment clause, among other rights, only applied to limit the actions of Congress and the Federal government. The Bill of Rights did not apply at the state level. States were still able to pass laws that would infringe on freedom of the press, free exercise of religion, and the establishment of religion, or violate any of the other rights that we take for granted today.

But freedom has no greater opposite than slavery, where the body, mind, and soul of individuals are completely subjugated to others, yet this was the status of a significant number of Americans during most of the first century of existence as a republic, as the citizens of the states were blocked from receiving the full benefit of the Bill of Rights and the slave states continued to allow the degradation of human life as a matter of policy and of “right.”

By 1860, the U.S. Census reported that there were nearly 4 million slaves, representing 12.6% of the entire population. Finally, also in 1860, after decades of relentless attacks on slavery by the abolitionist movement, and a growing sense of moral outcry, Republican Party candidate Abraham Lincoln spoke out openly in support of a nationwide ban of slavery – a position that the Southern states viewed as “unconstitutional.” In their view, after all, Lincoln was a threat to their state sovereignty.

In January 1861, just before Lincoln was to be inaugurated in March, seven of the slave states seceded from the United States to form their own nation where slavery would remain. After Southern forces attacked a Union supply fort located on a small island in Charleston Harbor, North Carolina, the nation split and the war was fought between the states. After four years of combat, and the deaths of more than 620,000 soldiers on both sides and absolute destruction of the industrial infrastructure of the South, the nation began its process of Reconstruction which amended the Constitution in order to restore the Union and guarantee civil rights to the freed slaves.

After the Civil War, as a condition of returning to the Union the states that seceded were required to adopt three Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery. The Fourteenth Amendment, which I will focus on in this article, applied the Bill of Rights to the States, and the Fifteenth prohibited discrimination in voting rights based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” All three were ratified by the states between 1865 and 1870.

The Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1 states:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The dehumanizing effects of slavery persisted even after these Amendments were passed, and the legal advances were undermined by Jim Crow laws that discriminated against African-Americans in the South, and the U.S. Supreme Court decisions in the Slaughter-House cases in 1873. Despite a rocky start in the years following the Civil War and though obfuscated in the decades that filed, these Amendments finally fulfilled their promises of providing all Americans with the freedoms promised in the Bill of Rights.

Make no mistake about it, freedom in America is a recent thing. In fact, freedom has existed in American law for only 50 years or so. Despite all the beautiful words of the Founders describing freedom, it was only when we were all free that freedom truly came to fruition in America. Freedom is young.

In fact, it wasn’t until Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U.S. 1 (1947) that the Court first used the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to apply the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the laws of a state.

The Everson case involved a claim brought by a taxpayer who claimed that a New Jersey program that reimbursed parents of children attending private religious schools violated the constitutional prohibition against state support of religion. The Justices were split on whether the issue brought by the taxpayer actually amounted to state support of religion, but both the majority and dissent agreed that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment meant that the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment did not only apply to Congress, but to the states.

The true benefits of these Amendments as a means for reducing racial inequality was not realized until nearly a century after those three Amendments had been passed when Supreme Court issued a ruling against segregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The cases and statutes that were put in place during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s finally gave the Constitutional guarantees of freedom some teeth and required the states to recognize them in law and practice thereafter.

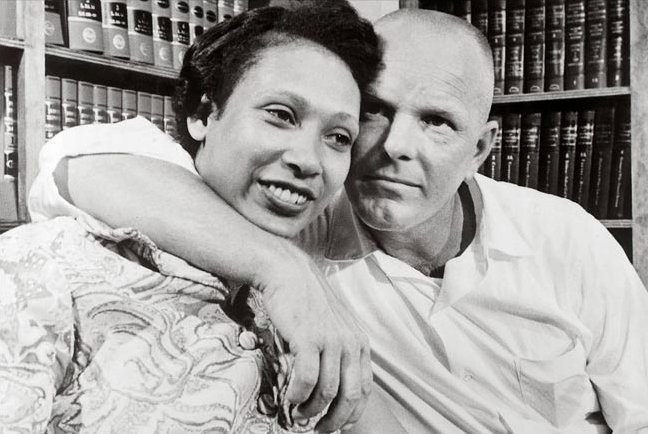

Because of ongoing state-level and local civil rights abuses, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately heard a number of cases brought by citizens who had been denied their civil rights. In 1967, the Court heard the case of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1. In that case, Mildred Loving, an African American woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, had been sentenced to a year in prison in Virginia for marrying each other in violation of the state’s “Racial Integrity Act of 1924.”

[perfectpullquote align=”right” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival. U.S. Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia[/perfectpullquote]

Justice Earl Warren drafted the unanimous opinion of the Court:

Marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival…. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.

The “civil right of marriage” language in Loving v. Virginia served as a precedent for the 2015 decision in Obergefell v. Hodges which overturned state-level restrictions on same-sex marriage.

There are thousands of volumes that cover the history of the Bill of Rights. But there are still those who see themselves as fighting the Civil War yet again, and contemplate that they are living in a pre-Fourteenth Amendment world. They assert that the states do not have to extend rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution or Federal Courts to their citizens. In fact, there are many who argue that the Reconstruction Amendments are not legitimate law, or ignore them altogether.

In the current fight over the right of Rowan County Clerk Kim Davis to refuse to acknowledge or sign off on same-sex marriages under her “authority,” the argument has often turned to whether the Supreme Court had the power to uphold same-sex marriage.

Mike Huckabee, a presidential candidate, was recently interviewed by radio host Michael Medved (listen to recording at Buzzfeed) and he compared the legalization of same-sex marriage to the Dred Scott decision which had upheld slavery.

“Michael,” Huckabee said, “the Dred Scott decision of 1867 still remains to this day the law of the land which says that black people aren’t fully human. Does anybody still follow the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision?”

What Huckabee does not realize, or maybe refuses to acknowledge, is that Dred Scott and slavery were actually overturned when the states passed the Reconstruction Amendments. In fact, the Thirteenth Amendment expressly forbids slavery. Although Huckabee places the argument in the context that the Court has never overturned Dred Scott, it also is indicative of the ongoing sense among some that the Reconstruction Amendments can be done away with altogether. If these Amendments disappear, so does the Supreme Court’s power to rule in Obergefell. It is as if the Civil War was never fought.

The argument that the Federal courts have no power to address civil rights issues or even enforce prohibitions on state-level Free Exercise or Establishment Clause violations seems to be gaining steam among social conservatives who want the Federal Courts to stay out of out the way of the states.

Another way that politicians have sought to circumvent the Fourteenth Amendment and the Federal Court system is by using the Article III powers of the U.S. Congress to control what cases Federal judges can hear. In 2004, after a Federal Court ordered him to remove a Ten Commandments monument from the State Judiciary Building, Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Roy Moore and his attorney Herb Titus proposed that Congress pass something called the “Constitution Restoration Act” (CRA).

The purpose of the act, according to Moore, was “to restrict the appellate jurisdiction of the United States Supreme Court and all lower federal courts to that jurisdiction permitted them by the Constitution of the United States. The acknowledgment of God as the sovereign source of law, liberty, and government …. The acknowledgment of God is not a legitimate subject of review by federal courts.”

By removing Establishment Clause cases from the Federal judiciary, any question related to Moore’s violation of the Establishment Clause would have stopped with Moore’s Supreme Court panel at the state level. (You can read more about the Constitution Restoration Act in the March / April 2006 issue of Liberty Magazine.)

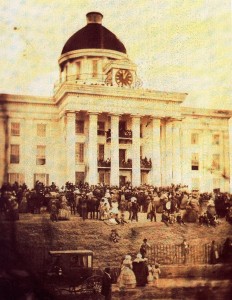

A few years ago, I had the privilege of visiting the Alabama State Capitol building in Montgomery. First constructed in 1850 the building serves as a geographical reminder of the struggle between civil rights and states’ rights. In 1861 after Alabama seceded the building became the first Confederate Capitol. A star on west side porch overlooking Dexter Avenue marks the place where Jefferson Davis stood when he was sworn in as the President of the Confederate States. At the end of the civil war, tens of thousands of Union troops had marched up Dexter Avenue and planted the flag of the United States on the capitol.

That star is also the place where Alabama Governor George Wallace declared “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” while looking directly at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where Martin Luther King, Jr. had organized the bus boycott in non-violent protest. The Selma to Montgomery March in 1965 ended on the steps of the capitol building where Dr. King and thousands of others attempted to hand-deliver their petition for equal protection under the law to Governor Wallace.

If you walk down the western steps toward Dexter Avenue, the first building you’ll see facing the street on your left is the Dexter Avenue Baptist church. The third building is the Alabama State Judiciary where Judge Roy Moore again protested Federal Law and demanded the right to post the Ten Commandments monument in violation of the Establishment Clause. He refused to allow any other monuments, including other religious monuments or a monument to Martin Luther King, Jr. to be posted next to the Commandments because those others would violate the “sovereignty of God.”

Religious liberty and civil rights go hand-in-hand and when civil rights are denied, religious liberty is also seriously threatened.

When filing cases against state-level encroachments on religious liberty, we access the Federal Court jurisdiction through the same portal of the Fourteenth Amendment through which other Civil Rights are reached. Without the Fourteenth Amendment, the local government would be the ultimate arbiter of what freedoms, if any, could be enjoyed under the Bill of Rights.

The next time that somebody claims that “unelected lawyers” sitting on the U.S. Supreme Court or another Federal court “make” crucial Civil Rights laws in America, and instead promotes some kind of alternative that puts local or state authorities in charge of your freedoms, it may be time for a history lesson.

###

Thus is excellent information. Something everyone who is concerned about the religious right needs to read.

This article is proof that this site is a true leader when it comes to religious liberty advocacy. Where is the church with this information?

I agree with J. Blakely’s comments. Our church should be doing more to get this type of information into the hands of our members.