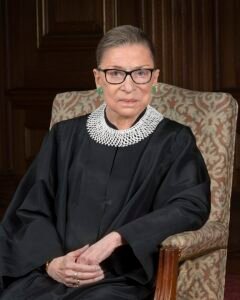

[dc]Y[/dc]esterday, Ruth Bader Ginsburg died from cancer at the age of 87. A Clinton appointee, Ginsburg, the second woman to serve as a Supreme Court justice, served on the Supreme Court from August 10, 1993, until her death. Here is a brief survey of some of her decisions in cases involving the religion clauses of the First Amendment. Ginsburg wrote few opinions on the religion clauses, with the exception of some notable dissents, but she frequently joined her colleagues who supported the strong separation of church and state.

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) –

Justice Ginsburg joined the majority in this 6-3 decision that the Federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) only applied to actions of the Federal Government and not states. The Court found that Congress had exceeded its power in enacting RFRA, which provided a strict scrutiny standard to any government actions (state or federal) that substantially burdened the free exercise of religion.

Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995) –

Justice Ginsburg joined Justice Souter’s dissent. The majority ruled that it was unconstitutional for a state university to withhold funding from student religious publications when the university paid for similar secular student publications. Thus, the funding did not violate the Establishment Clause. The Court found that the student activities funding at the University of Virginia was neutral for purposes of opening “a forum for speech and to support various student enterprises, including the publication of newspapers, in recognition of the diversity and creativity of student life.”

The dissent, joined by Ginsburg, argued that required a state university to fund the “Wide Awake” evangelistic publication through student fees violated the Establishment Clause and that religious publications were distinct from secular publications.

Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997) –

Ginsburg joined Souter’s dissent from this 5-4 decision, written by O’Connor. The majority found that a state-sponsored education initiative allowing public school teachers to provide instruction at religious schools was constitutional if the material was secular and neutral and did not lead to “excessive entanglement” between government and religion.

Souter, joined by Ginsburg, argued that using public funds to pay public school teachers on religious school campuses violated the Establishment Clause. Souter argued that there was not enough reason to overturn the Aguilar and Ball cases that required states to consider how to monitor teacher activities on religious campuses (Aguilar) and whether the public school teachers would be in a position where they could be indoctrinating students in religion (Ball).

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000) –

Ginsburg joined Justices Kennedy, Stevens, O’Connor, Souter, and Breyer in the majority opinion which ruled that a policy that permitted student-led, student-initiated prayer at high school football games violated the Establishment Clause. In his dissent, Chief Justice Rehnquist, joined by Scalia and Thomas wrote that the majority opinion “bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life” and argued that the Establishment Clause should not apply when the speech in the prayer would be that of private individuals, not the public school itself.

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002) –

Ginsburg joined Justice Stevens’ dissent from the majority that decided 5-4 that an Ohio school voucher program did not violate the Establishment Clause. The majority applied a newly minted Private Choice Test which found that the program (1) had a valid secular purpose; (2) the money went directly to the parents and not the schools; (3) benefited a broad class of beneficiaries; (4) was neutral concerning religion; and (5) there were adequate non-religious options. The majority differentiated this decision from the Lemon test because, in Lemon, the funding went straight to the schools, but in Zelman, the funding went to the parents. The dissent argued, however, that the fact that funding would go to religious instruction itself would violate the Establishment Clause.

Stevens’ dissent, citing Agostini v. Felton, noted that the funding violated the Establishment Clause and that “constitutional lines have to be drawn, and on one side of every one of them is an otherwise sympathetic case that provokes impatience with the Constitution and with the line. But constitutional lines are the price of constitutional government.”

Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005) –

Ginsburg joined in two dissents from the plurality that ruled 5-4 that a Ten Commandments monument that had been erected in 1961 on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol did not violate the Establishment Clause because it represented historical value and not just religious value.

Ginsburg joined Justice Stevens, who argued that the Establishment Clause “created a strong presumption against the display of religious symbols on public property.” Stevens argued that the majority’s decision “makes a mockery of the constitutional ideal that government must remain neutral between religion and irreligion. If a State may endorse a particular deity’s command to ‘have no other gods before me,’ it is difficult to conceive of any textual display that would run afoul of the Establishment Clause.”

She also joined Justice Souter’s dissent that the Texas capitol was the “civic home” of the State’s citizens, and “[i]f neutrality in religion means something, any citizen should be able to visit that civic home without having to confront religious expressions clearly meant to convey an official religious position that may be at odds with his own religion, or with rejection of religion.”

Souter also rejected the idea that the historical value of a particular monument meant it should not be scrutinized. He wrote that the State’s argument “seems to be that 40 years without a challenge shows that as a factual matter, the religious expression is too tepid to provoke a serious reaction and constitute a violation. Perhaps, but the writer of Exodus chapter 20 was not lukewarm….”

McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, 545 U.S. 844 (2005) –

Ginsburg joined the majority in this 5-4 ruling, issued at the same time but reaching an opposite conclusion as Van Orden v. Perry, that a Ten Commandments display at a courthouse in Kentucky was not constitutional because it lacked the historical aspect present in the concurrently decided Van Orden case.

The Court held that the government must be neutral both between one religion and another as between religion and secularism.

Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) –

Ginsburg joined in Stevens’ “Concurrent / Dissent” partially agreeing with this 5-4 decision holding that the free speech clause of the First Amendment extends to corporations, labor unions, and other associations, and that attempts to limit speech constituted prior restraint. Stevens agreed that parts of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act were constitutional, but disagreed with the theory that a corporation is a person. According to Stevens, corporations were made up of individuals who did have free speech rights, but that corporations were simply collections of people without independent free speech rights.

This case formed the background for the Hobby Lobby case, in which the Court found that free exercise of religion rights extend beyond individuals to corporations and associations.

Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011) –

Ginsburg joined Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority opinion in this 8-1 decision which held that people protesting on a public sidewalk about a public issue could not be held civilly liable for the tort of emotional distress even if the speech were outrageous. Members of the Westboro Baptist Church had protested at the military funeral of a Marine, Matthew Snyder, who died in the Iraq war. They posted statements on their website, denouncing how Snyder’s parents had raised him, and displayed placards with offensive comments. Snyder’s father sued for defamation, and a jury found $10.9 million in damages. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roberts stated, “What Westboro said, in the whole context of how and where it chose to say it, is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment and that protection cannot be overcome by a jury finding that the picketing was outrageous.”

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 565 U.S. 171 (2012) –

Ginsburg joined the other Supreme Court justices in ruling unanimously that federal discrimination laws do not apply to the way that religious organizations select religious leaders. Chief Justice Roberts, on behalf of the Court, wrote, “the Establishment Clause prevents the Government from appointing ministers, and the Free Exercise Clause prevents it from interfering with the freedom of religious groups to select their own.”

Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. 565 (2014) –

Ginsburg dissented from the majority opinion in this 5-4 decision that a city may permit volunteer chaplains to open city council sessions with prayer.

She joined Justice Kagan’s dissent, along with Justices Breyer and Sotomayor. Kagan wrote, “When the citizens of this country approach their government, they do so only as Americans, not as members of one faith or another. And that means that even in a partly legislative body, they should not confront government-sponsored worship that divides them along religious lines.”

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ____ (2014) –

Ginsburg filed a dissenting opinion from this 5-4 decision. The majority ruled that a for-profit corporation can claim a free exercise of religion right when it ruled that closely held for-profit corporations could be exempted from federal law, that corporate owners object to, if there is a less restrictive means of furthering the law’s interest. The majority used the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to find that the corporation had the right to be exempt from a neutral law of general applicability.

Ginsburg argued that the Court had not correctly applied RFRA, which was originally intended to restore the “compelling interest test” instead of the “least restrictive means” test. She wrote that the compelling interest test from Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963), was “a workable test for striking sensible balances between religious liberty and competing prior governmental interests.”

She then stated that RFRA applied to “a person’s exercise of religion,” and that a for-profit corporation was not a “person.” Ginsburg wrote, “the exercise of religion is characteristic of natural persons, not artificial legal entities.” She continued, citing Justice Stevens’ dissent that she had joined in Citizens United, that corporations “have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires.”

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015) –

Ginsburg joined the majority opinion, finding that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry under the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. All states were now required to perform and recognize the marriages of same-sex couples. Kennedy, on behalf of the majority, wrote, “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc., v. Comer, 582, U.S. ____ (2017) –

Ginsburg joined Sotomayor in dissenting from this 7-2 decision finding that a Missouri playground resurfacing grant program that denied a grant to a religious school while providing grants to similarly situated non-religious groups violated the Free Exercise Clause. The Court found that a state could distinguish between religious and non-religious uses but not between religious and non-religious entities. The Court ruled that the State of Missouri, which had a state constitutional prohibition on aid to religious schools, had no basis for having a stronger law separating church and State than that already found within the U.S. Constitution.

Joined by Ginsburg in her dissent, Sotomayor wrote that “This case is about nothing less than the relationship between religious institutions and the civil government – that is, between church and State. The Court today profoundly changes that relationship by holding, for the first time, that the Constitution requires the government to provide public funds directly to a church. Its decision slights both our precedents and our history, and its reasoning weakens this country’s longstanding commitment to a separation of church and State beneficial to both.”

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. ___ (2018) –

Ginsburg, joined by Sotomayor, dissented from the majority in this 7-2 “wedding cake case” decision that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had not exercised religious neutrality when it found that baker Jack Phillips had impermissibly discriminated against a same-sex couple when he refused to prepare a cake for their wedding ceremony. The decision did not address the highly anticipated issue of the intersection between anti-discrimination statutes and whether the baker had free speech or free exercise of religion rights.

In her dissent, Ginsburg wrote that the baker had impermissibly discriminated against potential customers based on their sexual orientation and that majority had incorrectly opined that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had shown hostility to religion when it fined Phillips but not bakeries that had refused to bake a cake with offensive “words or images.” In this case Phillips had not been asked to decorate a cake a certain way but had refused to sell a visually neutral cake if it would be used for a same-sex ceremony.

Trump v. Hawaii, 585, U.S. ___ (2018) –

Ginsburg joined Sotomayor’s dissent in which the majority applied the “rational basis test” and found that the President had executive authority to restrict travel in the United States by people from several nations. There was an inference that this third attempt at a travel ban sought to circumvent claims that the prior attempts stemmed from religious animus.

Sotomayor focused on the Establishment Clause issue and argued that the Court should have applied a higher level of scrutiny than the rational basis test when the President had issued the ban because, in Trump’s terms, the reason for the ban was that it would be a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.”

American Legion v. American Humanist Assn., 588 U.S. ___ (2019) –

Ginsburg, joined by Sotomayor, dissented from the decision that a cross on public property honoring World War I veterans did not violate the Establishment Clause. The majority found that the cross had taken on a secular meaning. This historical importance exceeded the religious symbolism.

Ginsburg argued that the cross is “the foremost symbol of the Christian faith,” and the display on public land “elevates Christianity over other faiths, and religion over nonreligion.”

Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 591 U.S. ____ (2020) –

Ginsburg joined Kagan in dissenting from the June 30, 2020, 5-4 ruling that a Montana “no aid to religious school” rule impermissibly discriminated against religious schools, and that Montana’s interest in the separation of church and State was “not compelling.” The exclusion of religious schools from the tax credit program violated the free exercise rights of religious schools and parents.

Ginsburg wrote that when the Montana Supreme Court invalidated the entire scholarship program, there was no longer a triable issue before the Supreme Court.

Holding: The Religious Freedom Restoration Act does not apply to state and local governments unless explicitly enacted by state legislatures.

Holding: It is unconstitutional for a state university to withhold funding from student religious publications when the university funds similar secular student publications.