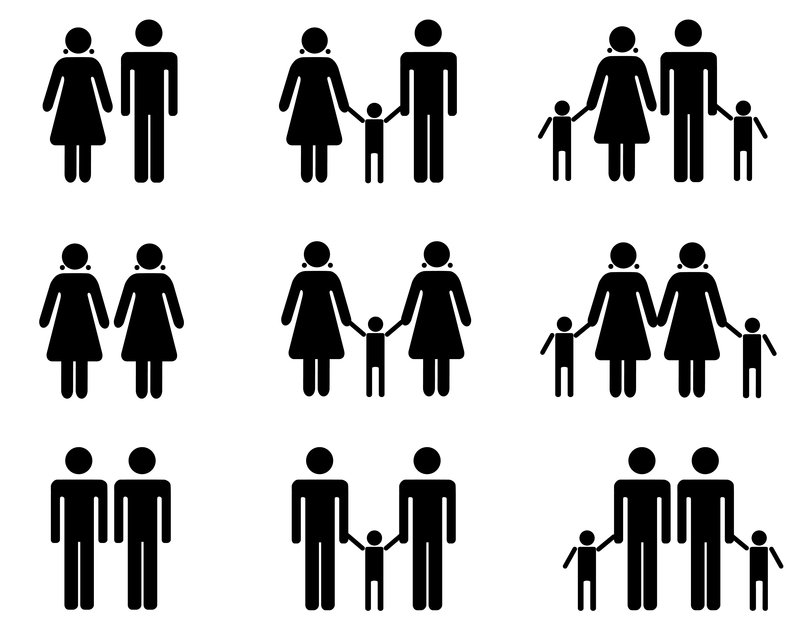

[dc]O[/dc]n April 28, 2015, the Supreme Court heard arguments on whether states can ban same-sex marriages, and if so, whether states that ban same-sex marriages must recognize same-sex marriages from states that perform them.

After the Court issued narrow rulings in 2013, finding that private proponents of California’s constitutional ban on same-sex marriage did not have standing to represent California when the state government refused to appeal a federal judge’s decision overturning the ban (Hollingsworth v. Perry), and that a portion of the federal Defense of Marriage Act that prohibited a federal tax exemption to the surviving spouse of a state-recognized same-sex marriage was unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor), the Court now has the opportunity to decide whether same-sex marriage will be legalized.

After hearing the arguments, it is hard to tell how the Court is going to rule in Obergefell v. Hodges, and I believe that the implications of the decision may extend beyond the four states involved in the case, which included Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee.

Although many Americans have voted for bans against same-sex marriage because of moral qualms, religious concerns, or simply because of tradition, arguments that play to public opinion do not typically play well in the courtroom.

It has been very difficult for opponents of same-sex marriage to articulate arguments that promote marriage in such a way that it honors love and commitment between spouses but at the same time excludes same-sex couples. If anything, same-sex couples who want to be married would also embrace the values of love and commitment which form the basis of most marriages. Arguments that same-sex couples should not be married because of alleged increased infidelity or promiscuity have fallen flat.

The only argument that has gained any traction is the idea that same-sex couples are unable to biologically have their own children, and that is what the attorney arguing for the state of Michigan relied upon. John Bursch, a former solicitor general of Michigan, is a brilliant 42-year-old attorney who has argued before the Court eight times since 2011, which is 6% of all the cases the Court heard during that period, on topics ranging from what phone companies can charge competing networks to defending Michigan’s felony statute for the non-payment of child support.

Yet Bursch struggled to defend Michigan’s ban on same-sex marriage. He argued that the voters should have “fundamental liberty” in deciding what marriage means but ignored Justice Kagan’s argument that there is liberty in allowing people to choose who they want to marry. He argued that marriage is a practical arrangement designed to bond children to their biological mothers and fathers, and is not “all about emotion and commitment.”

Justice Kagan raised the question of whether marriage should be denied to people who don’t want children, and Bursch responded, “But, Justice Kagan, even people who come into a marriage thinking they don’t want to have children often end up with children.”

Bursch followed this train of thought to an absurd degree, goaded on by Justice Ginsburg who asked whether a 70-year-old couple should be allowed to marry. Bursch’s answer was cringeworthy. “Well, a 70-year-old man, obviously, is still capable of having children and you’d like to keep that in marriage.”

Although he may not have had to raise the issue, Bursch did not address the point that Justices Scalia, Alito, and anticipated swing-vote Kennedy had raised involving the notion that marriage has not changed “for millenia” and that same-sex marriage is a relatively new institution, with the first country to legalize it being the Netherlands in 2001.

The legal standard for addressing same-sex marriage has not yet been firmly established, with proponents of legalization arguing that the compelling state interest test needs to apply as it denies a fundamental right, and opponents arguing that a rational basis test applies as the state has broad discretion to determine who can marry.

In the wake of the arguments on Question 1, Question 2, regarding same-sex marriage across state lines was denouement. Question 2 is only relevant if the Justices, more likely on the strength of the many briefs that have been filed rather than the short oral argument, decide that it is legal for states to decide to ban same-sex marriage. Douglas Hallward-Driemeir, appearing for the petitioners, argued that marriage needs to be portable in a mobile society. Counsel for the state of Tennessee, Joseph Whalen, argued that the “full faith and credit” Clause of Article IV does not apply to state statutes, but rather judicial decisions. Justice Sotomayor asked whether marriage certificates should carry weight from state-to-state like birth certificates.

One of the issues that has not been addressed to the extent it perhaps should be, is what happens if the Supreme Court decides that each state can decide whether to allow for same-sex marriage.

In Hollingsworth v. Perry, the Court decided based on standing, and did not reach the merits of whether the California constitution amendment (Ballot Proposition 8, passed in 2008) banning same-sex marriage was in fact legal under the United States Constitution. The California amendment had been declared unconstitutional by a federal judge and even the California Supreme Court could not overturn a provision of the California constitution. Therefore, if the Supreme Court reverts the issue to the states, would the various federal decisions that legalized same-sex marriage, not only in California, but in many other states likewise disappear? How would this affect existing same-sex marriages in these states?

It is difficult at this stage to predict which way the Court is going to rule, although the votes of Justices Ginsburg and Kagan are predictable, with each having performed same-sex weddings. Justice Scalia and Justice Alito will likely find that the long history of marriage being defined in society as being between a man and a woman justifies moving slowly, if at all, toward affirming same-sex marriage, and that the states should set the pace, not the Court. But this is likely to be a tight decision, with a 5-4 vote riding on Justice Kennedy whose questions imply a take-it-slow approach.

The concept of group rights to exclude versus an individual right to marry carries forward into the various wedding-related services that have been in dispute recently. While same-sex proponents argue that others should not be able to decide for them who to marry, they may also want to carry this logic forward and provide accommodation for those who, not due to animus, but rather due to sincerely-held religious beliefs, do not want to participate in providing services related to same-sex weddings. The rights of individuals and groups intersect at these times, and the diverse beliefs of all involved can be protected if both sides are willing to find solutions.

In the wake of the current arguments about Religious Freedom Restoration Acts, which are primarily a state function, much like marriage would be if the Court decides that one size does not fit all states, then it is likely that RFRAs will be the tool used to protect those who, for religious reasons, do not wish to participate in same-sex marriage. If the Court decides that same-sex marriage is a federally-protected right across the country, we can expect that Congress will look for a national resolution, which may be a retread of RFRA but geared toward addressing issues of marriage and individual rights of conscience.

With all the pitfalls that can be conjured up in answer to the two questions that were posed on Tuesday, the Court may find a way to avoid taking any action, leaving everything as it is right now, with the Circuit Courts of Appeal being able to decide whether or not same-sex marriage is constitutional.

###

Holding: The Constitution guarantees a right to same-sex marriage.

Holding: Private proponents of California's constitutional ban on same-sex marriage did not have standing to represent California when the state government refused to appeal a federal judge's decision overturning the ban.

Holding: A portion of the federal Defense of Marriage Act that prohibited a federal tax exemption to the surviving spouse of a state-recognized same-sex marriage was unconstitutional.