[dc]A[/dc]s part of our series on Religious Freedom Restoration Acts, it might be helpful to review the legal history of where we started and where we could be going.

Keeping the Sabbath and a Compelling State Interest

When Adeil Sherbert, a South Carolina textile mill worker and a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, was terminated from her employment because she refused to work on Saturdays, she tried to find another job. She applied to many different employers but none would offer her a job and accommodate her Sabbath. So she applied for state unemployment benefits.

South Carolina denied her unemployment benefits because they thought she was unreasonable for refusing jobs even if they would require her to work Saturdays. The case made its way to the State Supreme Court which agreed that the state should not be forced to pay her unemployment benefits.

Sherbert then appealed her case to the U.S. Supreme Court which reached a different conclusion in 1963. In the decision, Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) written by Justice Brennen, the Court ruled that even though Sherbert was a member of a minority faith and had not been singled out for discrimination by a neutral law, the state’s requirement that she abandon her faith in order to get benefits imposed a significant burden of Sherbert’s ability to freely exercise her faith. The Court found that there was no compelling state interest which justified the burden on her First Amendment right to free exercise of religion.

Brennan wrote that “to condition the availability of benefits upon this appellant’s willingness to violate a cardinal principle of her religious faith effectively penalizes the free exercise of her constitutional liberties.”

The Sherbert Court implemented a three-prong test, to use when determining whether the government has violated an individual’s right to the free exercise of religion.

- First, the courts must determine whether there has been a burden on the individual’s free exercise of religion. If the government requires a choice that pressures the individual to forego a religious practice, whether by imposing a penalty or withholding a benefit, then there is a burden.

- Secondly, if there is a burden, the court must investigate whether it is constitutional. Under this test, the government may still impose a burden if there is (1) a compelling state interest that justifies the infringement; and (2) no alternative form of regulation can avoid the infringement and still achieve the state’s goal.

The Sherbert Test, named after a Seventh-day Adventist mill worker, remained the standard until 1990 when a very similar case made its way to the Court.

The Supreme Court Erases the Sherbert Test

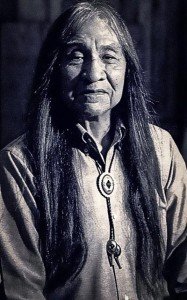

In the 1980s, Alfred Smith and Galen Black, both members of the Native American Church, were terminated from their employment as drug counselors because they used peyote, an illegal entheogen drug, as part of their beliefs. They applied for unemployment benefits with the State of Oregon. The state denied them unemployment benefits because they were drug counselors who had been fired for using an illegal drug.

In 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a decision that because the peyote law was a “neutral law of general applicability,” no exception should be made for Smith and Black or other members of the Native American Church.

Scalia wrote that allowing these kind of exemptions would allow an individual, “by virtue of his believes, ‘to become a law unto himself.'” This, wrote Scalia, “contradicts both constitutional tradition and common sense. To adopt a true ‘compelling interest’ requirement for laws that affect religious practice would lead towards anarchy.” Employment Division v. Smith, 494 U.S. at 885 (1990).

Under this analysis, not only would Mr. Smith and Mr. Black lose, but so would Ms. Sherbert when the Smith court effectively eliminated the Sherbert Test by ruling that if a law is generally applicable to everybody, there is no need for the state to make exemptions for religious purposes.

Religious Freedom Restoration Act Restores Sherbert Test

The Smith decision frightened a broad coalition of Americans, ranging from the ACLU to a wide variety of religious groups who sensed that the very essence of the Free Exercise Clause was now in danger of collapse. In response, the U.S. Congress acted quickly and nearly unanimously to restore the Sherbert Test.

On November 16, 1993, President Clinton signed into law the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (Federal RFRA) which had been sponsored by Senator Ted Kennedy and Congressman Chuck Shumer. In his signing statement, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/WCPD-1993-11-22/pdf/WCPD-1993-11-22-Pg2377.pdf , the President noted that the bill had passed the U.S. Senate by a vote of 97 to 3 and through the House of Representatives by a voice vote.

The President continued, “We all have a shared desire here to protect perhaps the most precious of all American liberties, religious freedom. Usually the signing of legislation by a President is a ministerial act, often a quiet ending to a turbulent legislative process. Today this event assumes a more majestic quality because of our ability together to affirm the historic role that people of faith have played in the history of this country and the constitutional protections those who profess and express their faith have always demanded and cherished. The power to reverse legislation by legislation, a decision of the United States Supreme Court, is a power that is rightly hesitantly and infrequently exercised by the United States Congress. But this is an issue in which that extraordinary measure was clearly called for. As the Vice President said, this act reverses the Supreme Court’s decision Employment Division against Smith and reestablishes a standard that better protects all Americans of all faiths in the exercise of their religion in a way that I am convinced is far more consistent with the intent of the Founders of this Nation than the Supreme Court decision.”

President Clinton then explained the reason for RFRA:

“More than 50 cases have been decided against individuals making religious claims against Government action since that decision was handed down. This act will help to reverse that trend by honoring the principle that our laws and institutions should not impede or hinder but rather should protect and preserve fundamental religious liberties. . . . What this law basically says is that the Government should be held to a very high level of proof before it interferes with someone’s free exercise of religion. This judgment is shared by the people of the United States as well as by the Congress. We believe strongly that we can never, we can never be too vigilant in this work.”

In RFRA, Congress stated in its findings that a religiously neutral law could burden a religion as much as one that was intended to interfere with religion and that RFRA would confirm that “Government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.”

The Federal RFRA closely matched the Sherbert two-prong test and said that government could only intervene the exercise of religion when two conditions were both met:

First, the burden must be necessary for the “furtherance of a compelling government interest,” which is more than routine and does more than simply improve government efficiency.

Secondly, the rule must be the least restrictive means with which to further the government’s interest.

The Supreme Court Says RFRA Only Applies to the Federal Government

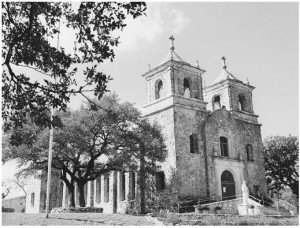

Although Congress intended RFRA to apply to the states, in 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court considered a dispute between a Catholic archbishop and the city of Boerne, Texas. Archbishop Flores wanted to enlarge his 1923 mission-style church, but the local zoning authorities denied the permit. Flores argued under the 1993 RFRA that the city’s action would fail the two-prong test. Flores said that because he could not modify the church property to accommodate a growing congregation, this represented a substantial burden on the church’s free exercise of religion, and there was no compelling state interest at stake in forcing him to keep his church looking a certain way;.

The case made its way through the courts, with a federal district judge striking down RFRA itself as unconstitutional. Although Flores won in the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, the city appealed to the Supreme Court where Justice Kennedy wrote an opinion City of Boerne v. Flores 521 U.S. 507 (1997), that ruled that Congress does not have the ability to change what a right is under the Constitution, only to enforce constitutional right, and that RFRA only applied to actions of the federal government.

Congress tried to repair this issue when it passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (2000) in which it used the Spending Clause of the Constitution to require that localities that receive federal funding have land use laws that accommodate religious freedom.

The Supreme Court also upheld the constitutionality of RFRA as it applies to federal law in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Unaio do Vegetal, 546 U.S. 418 (2006).

States Pass RFRA Bills to Restore the Sherbert Test

Even though the federal RFRA act did not apply to the states after the Boerne case was decided, Smith still applied, and legislatures in a number of states decided to pass their own RFRA statutes. As of April 2015, 20 states have passed RFRA statutes Alabama, Arizona, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana (into effect in July 2015), Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. (For links to the state RFRA laws, visit the Baptist Joint Committee’s State RFRA Tracker at http://bjconline.org/state-rfra-tracker-2015/#RFRATN )

Several states have, or are currently, considering RFRA bills this year including Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Michigan, Montana, North Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Of those states that have considered RFRA bills in 2015, only Indiana has enacted a bill this year although the Arkansas bill is currently headed to the governor.

For the most part, the state bills directly mirror the language of the federal statute. For instance, the Arkansas bill (HB 1228) states, ?A state action shall not substantially burden a person’s right to exercise of religion, even if the substantial burden results from a rule of general applicability, unless it is demonstrated that applying the substantial burden to the person’s exercise of religion in this particular instance: (1) Is essential to further a compelling governmental interest; and (2) Is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.”

Similarly, the Indiana bill states, ” ?A governmental entity may substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion only if the governmental entity demonstrates that application of the burden to the person: (1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.”

The Hobby Lobby Effect

While the earlier RFRA efforts passed without much notice, last year, the Supreme Court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ___ (2014) that the federal RFRA applied to protect the free exercise rights of owners of a 23,000 employee, “closely held” company who objected to a federal mandate that they provide their employees with health insurance that covered drugs that could potentially cause abortions. The Court ruled that corporations could assert their own “free exercise of religion” rights.

While the earlier RFRA efforts passed without much notice, last year, the Supreme Court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ___ (2014) that the federal RFRA applied to protect the free exercise rights of owners of a 23,000 employee, “closely held” company who objected to a federal mandate that they provide their employees with health insurance that covered drugs that could potentially cause abortions. The Court ruled that corporations could assert their own “free exercise of religion” rights.

After investigating the issue of whether the Religious Freedom Restoration Act was intended to cover corporations or just individuals and receiving a variety of responses from people involved in lobbying for and drafting the original legislation, it’s still not clear to me whether everybody involved in RFRA becoming law really thought that it could conceivably apply to large private corporations. Although the bill was bipartisan, the response to this question tends to fall along party lines although it is interesting that rights of corporations were not included in President Clinton’s speech.

Others argue that Hobby Lobby will not apply to states which may or may not determine that their own RFRAs are intended to apply to corporations, but one would suppose that corporations could raise Equal Protection Clause objections when individual people, but not “corporate” persons are protected by the law in light of the Supreme Court’s precedent.

Regardless of whether RFRA was intended to apply to corporations by some, none, or all of the drafters, Hobby Lobby added a new dimension to RFRA legislation. If the free exercise rights of corporate owners can prevail under a compelling interest test over and above the rights of their employees to federally required healthcare benefits, what can’t corporations do? Isn’t a government requirement that employers offer forms of healthcare a more compelling interest than a government requirement that conscientious objectors provide same-sex couples with wedding cakes? Will a state-level RFRA be a sword or a shield?

Although the Hobby Lobby court ruled that the decision was only applicable to the contraceptive mandate, others were not so convinced that it would not provide corporations with an inordinate amount of power. The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and National Center for Lesbian Rights withdrew their 20-year support for the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) which had recently been passed by the U.S. Senate claiming that its religious exemptions would provide employers with the right to discriminate under Hobby Lobby.

In an editorial for the Huffington Post posted March 31, 2015, Elliot Minceberg, a senior fellow for People of the American Way who was involved in the drafting and passage of RFRA in 1993 discussed the effect of Hobby Lobby on state RFRAs. (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/elliot-mincberg/hobby-lobby-comes-home-to_b_6980412.html)

Minceberg wrote that Hobby Lobby provided the justification for businesses to use state RFRAs to discriminate against the LGBT community: “Pass state RFRA laws and effectively grant a religious exemption claim from LGBT anti-discrimination laws and local ordinances, based on the Court’s rewriting of RFRA’s language. Indeed, in communicating with supporters about the Indiana RFRA law, the far-right Family Research Council specifically called it the ‘Hobby Lobby bill.'”

After Indiana passed a bill this year which could conceivably be used to protect the rights of religious business owners to discriminate against LGBTs, RFRAs in general have come under intense scrutiny and states such as Georgia, Texas, and even Indiana are scrambling to provide clarifications that the bills are not intended to permit anti-LGBT discrimination.

At the same time, others are concerned that the sincerely held religious beliefs of small business owners are being violated, even though New Mexico’s existing RFRA did not protect the owner of Elane Photography from being fined for refusing to photograph a same-sex marriage ceremony.

In the wake of Hobby Lobby, states are adding language that RFRAs cannot be used to protect religious believers against anti-discrimination laws, but if the right to practice one’s faith requires avoiding certain activities as a matter of religious conviction, this creates an incredibly complex and troubling scenario as constitutional free exercise rights could be subjected to statutory rights.

State RFRAs that track the federal statute should be sufficient to protect against discrimination. For instance, in Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983), a case decided while the Sherbert Test was still the standard, the Supreme Court ruled that the government had a compelling governmental interest in eradicating racial discrimination. The “Christian” university had initially banned African American students from attending, and then banned students who advocated for or engaged in interracial dating. When the IRS threatened the University’s tax exemption, the University sued. The Supreme Court ruled 8-1 against the school and Justice Burger applied the compelling interest test and wrote that “Government has a fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education … which substantially outweighs whatever burden denial of tax benefits places on [the University’s] exercise of their religious beliefs.”

Thus, in Bob Jones, discriminatory conduct by a religious institution did not survive the compelling interest test.

While the Bob Jones court made it clear that the decision only applied to universities, it is conceivable that a LGBT challenge against the tax-exempt status of conservative Christian universities may be brought under the same theory in the near future, particularly if the Court recognizes a right to same-sex marriage this summer.

The Way Forward

From a legal test that initially protected the rights of a Seventh-day Adventist textile mill employee to protecting the rights of a large corporation to deny insurance that covers contraceptive drugs for tens of thousands of employees, the compelling interest test may have been stretched to its breaking point.

But as politicians in Indiana have quickly learned, even if RFRA becomes law, market forces still come into play. If a law is perceived to promote discrimination, the media will highlight it, and a broad coalition of corporations and other entities will oppose the law and perhaps even boycott the state, costing millions. These factors will also play a role in shaping how narrowly tailored state RFRA legislation is and how it will be applied.

The two-part RFRA test provides a reasonable form of analysis that courts can use to determine whether the government has impermissibly infringed on free exercise rights of individuals and whether exemptions can be made that allow the government to meet its compelling interest in the least restrictive way possible. RFRA statutes that mirror the Sherbert test are a reasonable ways to maximize freedom while still protecting the compelling interests of the state.

Holding: The government must meet a strict scrutiny standard when burdening religious practice.