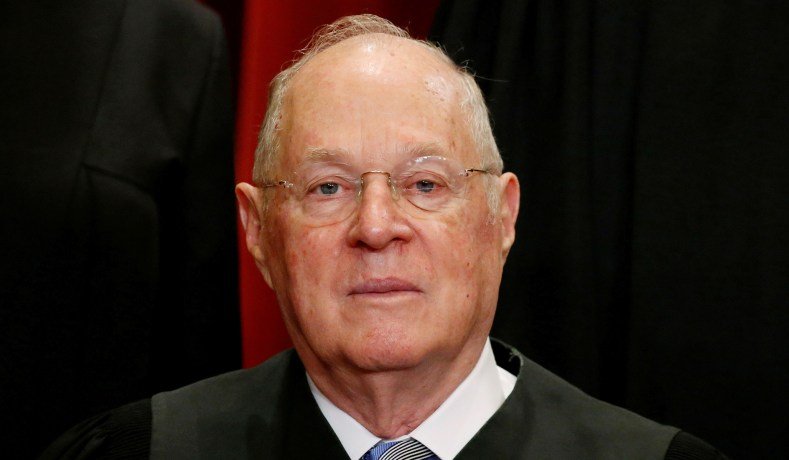

Last week, Reagan-appointed Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, 81, announced his retirement. After Justice O’Connor’s retirement in 2006, Kennedy was widely regarded as the Court’s “swing vote” whose decisions could sway the Court in either direction in close cases.

Within the next week, the President is expected to nominate Kennedy’s replacement. The following is a brief inventory of Justice Kennedy’s decisions on some key religion clause cases from his appointment in 1988 until his retirement in 2018.

Employment Division v. Smith, 505 U.S. 577 (1990) –Kennedy joined fellow Reagan-appointee Antonin Scalia’s majority opinion in the infamous peyote case finding that the free exercise clause of the First Amendment does not allow a person to use religion as a reason not to follow “a neutral law of general applicability.” The Court then invited the parties to use the legislative process to vet claims for religious exemptions rather than seek a constitutional exemption because using the Courts to overturn laws that adversely affected religious minorities could turn into “a system in which each conscience is a law unto itself.” In the decision, Scalia famously wrote that the Free Exercise Clause to argue against state regulations that adversely affect religion is a “luxury” that “we cannot afford.”

Scalia’s decision in Smith led Congress to pass the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) which was signed into law by President Clinton in 1993. The Court subsequently limited RFRA to federal actions in Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) and Gonzalez v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente , 546 U.S. 418 (2006). Since the Boerne decision, some states have attempted to pass their own RFRA laws to counteract the impact of Smith which continues to define what happens when the free exercise of religion conflicts with regulations. This case, legislative attempts to fix it (RFRA), and its progeny, have created an uncertain patchwork of confusion in which some exercise of religion (such as in Hobby Lobby, described below) is protected from adverse regulation and legislation while other religious exercise remains unprotected.

The Smith decision is currently being addressed in a string of cases involving wedding service providers who object to participation in weddings that they claim violate their faith.

Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992) – Scalia dissented from Kennedy who drafted the decision in this graduation prayer case in which the Court ruled that public schools may not sponsor clerics to conduct non-denominational prayer. In this case, the court found the State acting through schools cannot coerce students to face the social dilemma of either participating in or protesting a disagreeable prayer. Justice Kennedy wrote, “the embarrassment and intrusion of the religious exercise cannot be refuted by arguing that the prayers are of a de minimis character, since that is an affront to the rabbi and those for whom the prayers have meaning, and since any intrusion was both real and a violation of the objectors’ rights.”

In Scalia’s view, the only way that the government could violate the Establishment Clause would be if the state were to penalize those who refused to support or adhere to a particular religion. Scalia responded to the majority’s application of the “coercion test” stating that, “the Court – with nary a mention that it is doing so – lays waste a tradition that is as old as public school graduation ceremonies themselves, and that is a component of an even more longstanding American tradition of nonsectarian prayer to God at public celebrations generally. As its instrument of destruction, the bulldozer of its social engineering, the Court invents a boundless and boundlessly manipulable, test of psychological coercion.”

Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993) –Justice Kennedy wrote the majority decision in this case where the Court held that a Florida city ordinance prohibiting animal sacrifice as part of a religious ritual or ceremony was unconstitutional. The Court found that the ordinance specifically targeted the Santeria religion and did not pass the strict scrutiny test. In the decision, Kennedy stated, “religious beliefs need not be acceptable, logical, consistent or comprehensible to others in order to merit First Amendment protection.”

Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995) – Kennedy wrote the majority decision, finding that it was unconstitutional for a state university to withhold funding from student religious publications provided to similar secular student publications and that such funding did not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The Court found that the student activities funding at the University of Virginia was neutral for purposes of opening “a forum for speech and to support various student enterprises, including the publication of newspapers, in recognition of the diversity and creativity of student life.”

Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997) – Kennedy joined the majority of this 5-4 decision in finding that a state-sponsored education initiative that allowed public school teachers to provide instruction at religious schools if the material was secular and neutral and did not result in “excessive entanglement” between government and religion. This decision overturned the Court’s 1985 decision in Aguilar v. Felton which the Court concluded was no longer good law on the basis that Establishment Clause jurisprudence had changed in the past 12 years.

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000) – Kennedy joined Stevens, O’Connor, Souter, Ginsberg, and Breyer in the majority opinion which ruled that a policy that permitted student-led, student-initiated prayer at high school football games violated the Establishment Clause. In his dissent, Chief Justice Rehnquist, joined by Scalia and Thomas wrote that the majority opinion “bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life” and argued that the Establishment Clause should not apply when the speech in the prayer would be that of private individuals, not the public school itself.

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002) –Kennedy joined the majority in this 5-4 decision which found that an Ohio school voucher program did not violate the Establishment Clause. The majority applied a newly minted Private Choice Test which found that the program (1) had a valid secular purpose; (2) the money went directly to the parents and not the schools; (3) benefited a broad class of beneficiaries; (4) was neutral with respect to religion; and (5) there were adequate nonreligious options. The majority differentiated this decision from the Lemon test because in Lemon the funding went straight to the schools but in Zelman, the funding went to the parents. The dissent argued, however, that the fact that funding would go to religious instruction itself would violate the Establishment Clause.

Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005) – Kennedy joined the plurality in ruling 5-4 that a Ten Commandments monument that had been erected in 1961 on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol did not violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because it represented historical value and not just religious value.

McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, 545 U.S. 844 (2005) – Kennedy joined Scalia’s dissent from this 5-4 ruling, issued at the same time but reaching an opposite conclusion as Van Orden v. Perry, that found that a Ten Commandments displays at courthouses in Kentucky were not constitutional because they lacked the historical aspect present in the concurrently-decided Van Orden case. Scalia argued that the First Amendment does permit the government to acknowledge God, and in fact that it is permissible for the government to hold monotheistic religions such as Christianity, Islam, or Judaism in higher regard than other faiths. Wrote Scalia, “With respect to public acknowledgment of religious belief, it is entirely clear from our Nation’s historical practices that the Establishment Clause permits this disregard of polytheists and believers in unconcerned deities, just as it permits the disregard of devout atheists.”

Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010) – Kennedy drafted this 5-4 decision which held that the free speech clause of the First Amendment extends to corporations, labor unions, and other associations. This case formed the background for the Hobby Lobby case which found that free exercise of religion rights also extend to corporations and associations.

Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011) – Kennedy joined Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority opinion in this 8-1 decision which held that people protesting on a public sidewalk about a public issue could not be held civilly liable for the tort of emotional distress even if the speech was outrageous. In this case, members of the Westboro Baptist Church had protested at the military funeral of a Marine, Matthew Snyder, who died in the Iraq war, and had posted statements on their website denouncing the way that Snyder’s parents had raised him and displayed placards with offensive comments. Snyder’s father sued for defamation, and a jury found a total of $10.9 million in damages. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roberts stated, “What Westboro said, in the whole context of how and where it chose to say it, is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment and that protection cannot be overcome by a jury finding that the picketing was outrageous.”

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 565 U.S. 171 (2012) – The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that federal discrimination laws do not apply to the way that religious organizations select religious leaders. Chief Justice Roberts, on behalf of the Court, wrote, “the Establishment Clause prevents the Government from appointing ministers, and the Free Exercise Clause prevents it from interfering with the freedom of religious groups to select their own.”

Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. _____ (2014) – Kennedy wrote the majority opinion in this 5-4 decision finding that a city may permit volunteer chaplains to open city council sessions with prayer. In a separate concurrence, Scalia joined Justice Thomas stating that the case should have been dismissed outright since the Establishment Clause only applies to acts of Congress, and even then, only if the government engaged in “actual legal coercion” requiring tax money or imposing punishment for not participating.

Kennedy wrote, “To hold that invocations must be non-sectarian would force the legislatures sponsoring prayers and the courts deciding these cases to act as supervisors and censors of religious speech.”

He also wrote that legislative prayers might be impermissible if they “denigrate nonbelievers or religious minorities, threaten damnation, or preach conversion” or if the process for choosing a person to give the prayer is discriminatory.

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ____ (2014) – In this 5-4 decision, where Kennedy joined the majority opinion, the Court found that a for-profit corporation can claim a religious belief when it ruled that closely held for-profit corporations can be exempted from a federal law that its owners religiously object to if there is a less restrictive means of furthering the law’s interest. Ironically, the Court used RFRA to find that the corporation had the right to be exempt from a neutral law of general applicability. Citizens facing similar issues arising under state (not federal) law have no similar recourse unless their states have passed state-level RFRAs.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. ____ (2015) – Kennedy, joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, wrote the majority opinion in this case, finding that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry under the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, requiring all states to perform and recognize marriages of same-sex couples. Kennedy wrote, “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc., v. Comer, 582, U.S. ____ (2017) – Kennedy joined the majority in the 7-2 decision finding that a Missouri playground resurfacing grant program that denied a grant to a religious school while providing grants to similarly situated non-religious groups violated the Free Exercise Clause. The Court found that a state could distinguish between religious and non-religious uses but not between religious and non-religious entities. The Court ruled that the state of Missouri, which had a state constitutional prohibition on aid to religious schools, did not have a basis for having a stronger law separating church and state than that already found within the U.S. Constitution.

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, 584 U.S. ___ (2018) – Kennedy wrote for the majority in this 7-2 “wedding cake case” decision which found that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had not exercised religious neutrality when it found that baker Jack Phillips had impermissibly discriminated against a same-sex couple when he refused to prepare a cake for their wedding ceremony. The decision did not address the highly anticipated issue of the intersection between anti-discrimination statutes and whether the baker had free speech or free exercise of religion rights. Instead, Kennedy avoided this analysis completely and stated that the lower commission had violated its “obligation of religious neutrality” when a Commissioner had referenced Phillip’s religious beliefs in connection with the rhetoric used in the defense of slavery or the Holocaust.

Trump v. Hawaii, 585, U.S. ___ (2018) – Kennedy wrote a concurring opinion in this case which found that the President had executive authority to restrict travel in the United States by people from several nations. There was an inference that this third attempt at a travel ban was an attempt to circumvent claims that the prior attempts were baed on religious animus. Kennedy wrote that the President had the authority to issue the ban, but said the lower courts should review the ban itself to determine whether it was constitutional.

While his vote allowed the Presidential ban to stand, Kennedy wrote, “There are numerous instances in which the statements and actions of Government officials are not subject to judicial scrutiny or intervention. That does not mean those officials are free to disregard the Constitution and the rights it proclaims and protects. The oath that all officials take to adhere to the Constitution is not confined to those spheres in which the Judiciary can correct or even comment upon what those officials say or do. Indeed, the very fact that an official may have broad discretion, discretion free from judicial scrutiny, makes it all the more imperative for him or her to adhere to the Constitution and to its meaning and its promise.

“The First Amendment prohibits the establishment of religion and promises the free exercise of religion. From these safeguards, and from the guarantee of freedom of speech, it follows there is freedom of belief and expression. It is an urgent necessity that officials adhere to these constitutional guarantees and mandates in all their actions, even in the sphere of foreign affairs. An anxious world must know that our Government remains committed always to the liberties the Constitution seeks to preserve and protect, so that freedom extends outward, and lasts.”

Critics of the Kennedy concurring opinion charged that the Court had abrogated its responsibility to uphold the Constitution by allowing the Executive Branch to violate it under cover of executive authority.

Great material! This is really a good article because you always post grand related content and very informative information with powerful points. Just like the article I was looking for to read the article I found on your website. Thanks for sharing this piece of writing on this website. I want to tell you that it is very helpful for us. Thanks for sharing such an awesome blog with us. I want to visit again.