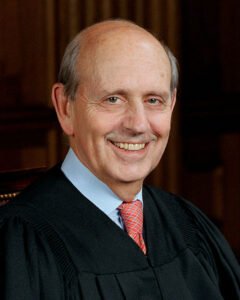

A Survey of Justice Stephen Breyer’s Religion and Law Decisions

Updated 5/2/2022 to include Justice Breyer’s written opinion in Shurtleff v. Boston.

By Michael D. Peabody

[dc]L[/dc]ate last month, Justice Stephen Breyer announced that he is retiring from the Supreme Court at the end of this term. Breyer, now 83, has served for more than 27 years. He was confirmed by the Senate by a vote of 87 to 9, a feat that may not seem possible in today’s partisan world. What is more impressive is that when Justice Byron White announced his retirement in 1993, President Bill Clinton called Utah Republican Senator Orin Hatch to ask who he thought would be a good match and pass the Senate, and Hatch recommended both Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Reflecting on this conversation in his memoirs, Hatch said, “I knew them both and believed that, while liberal, they were highly honest and capable jurists and their confirmation would not embarrass the president.” (Salt Lake Tribune, July 29, 2018).

Before his appointment to the Supreme Court, Justice Breyer was a law professor at Harvard University and took some time to serve on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973. In 1980 he became a judge on the First Circuit where he served until his nomination to the Supreme Court.

Breyer’s judicial philosophy was mostly pragmatic with an eye toward what he thought the Founders meant or would have done if they were facing the issues before the Court. This differed from Justice Antonin Scalia’s focus on adherence to the text itself. Breyer wrote a book, “Active Liberty: Interpreting our Democratic Constitution” in which he stated that the justices should not be afraid to take a pragmatic approach that considers both the purpose of the text and the consequences that a ruling will have in any given situation rather than limiting themselves to only the text.

Breyer’s philosophy is open to criticism that judges could decide based on what they would like to see happen rather than issue opinions based on the text of the law and precedent itself. But Breyer was able to issue balanced opinions that seemed focused on the practical realities of how his rulings could impact people while showing respect for the right of Congress and the states to develop and apply laws.

Breyer’s decisions in the major religion cases show that he took this practical approach seriously, and thus he could not be categorized as left- or right-leaning. His was the swing vote in the twin Ten Commandments cases of 2005, siding with the State of Texas to have a historical 40-year-old granite monument of the 10 Commandments on the capitol grounds, while opposing efforts by two Kentucky counties to make a religious point by posting framed Ten Commandments displays in courthouses.

He tended to support free exercise of religion, and dissented from the majority in Boerne v. Flores, arguing that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act should apply to the states. He was generally against state funding of religion, or state-sponsored religious activities because he felt that it was unnecessarily divisive, yet he agreed that a Lutheran School in Missouri should receive funding for a recycled rubber playground because that was a matter of health and safety, not religion.

What follows is a brief survey of some of his opinions in major cases involving the Religion Clauses from 1994 to the present:

Rosenberger v. University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995)

Breyer joined Souter, Stevens, and Ginsburg in dissenting from the 5-4 majority that ruled that it was unconstitutional for a state university to withhold funding from student religious publications when the university paid for similar secular student publications. Thus, the funding did not violate the Establishment Clause. The Court found that the student activities funding at the University of Virginia was neutral to open “a forum for speech and to support various student enterprises, including the publication of newspapers, in recognition of the diversity and creativity of student life.”

The dissent, joined by Breyer, argued that requiring a state university to fund the “Wide Awake” evangelistic publication through student fees violated the Establishment Clause and that religious publications were distinct from secular publications.

Wrote Souter, “The Court today, for the first time, approves direct funding of core religious activities by an arm of the State.”

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997)

Breyer joined O’Connor and Souter in dissenting from the majority in this 6-3 decision that the Federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) only applied to actions of the Federal Government and not states. The Court found that Congress had exceeded its power in enacting RFRA, which provided a strict scrutiny standard to any government actions (state or federal) that substantially burdened the free exercise of religion.

In the history of this case, the Supreme Court had ruled in Employment Division v. Smith (1990) that laws that adversely affected an individual’s free exercise of religion were permissible so long as they did not single out the person’s religion and were neutral on their face. This effectively eliminated the Free Exercise protections and Congress quickly passed the RFRA in 1993. Boerne v. Flores severely curtailed RFRA.

O’Connor wrote, and Breyer agreed, that Smith was wrongly decided and that the Free Exercise Clause “is best understood as an affirmative guarantee of the right to participate in religious practices and conduct without impermissible governmental interference, even when such conduct conflicts with a neutral, generally applicable law. Before Smith, our free exercise cases were generally in keeping with this idea: where a law substantially burdened religiously motivated conduct regardless of whether it was specifically targeted at religion or applied generally – we required government to justify that law with a compelling state interest and to use means narrowly tailored to achieve that interest.”

Since 1997, the Smith decision has been used to justify state laws that require people to do things that violate their personal religious beliefs. Justice Breyer was correct to dissent in Boerne and stand for the Free Exercise of Religion. But because the text of the Constitution limited the powers of Congress, the majority said Congress did not have power to overturn the Smith decision by requiring states to accommodate the free exercise rights of individuals when state laws were neutral and generally applicable.

Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203 (1997)

Breyer joined Souter’s dissent from this 5-4 decision. The majority decision, written by O’Connor, found that a state-sponsored education initiative allowing public school teachers to provide instruction at religious schools was constitutional if the material was secular and neutral and did not lead to “excessive entanglement” between government and religion.

Souter, joined by Bryer, argued that using public funds to pay public school teachers on religious school campuses violated the Establishment Clause. Souter argued that there was not enough reason to overturn the Aguilar and Ball cases that required states to consider how to monitor teacher activities on religious campuses (Aguilar) and whether the public school teachers would be in a position where they could be indoctrinating students in religion (Ball).

Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000)

Breyer joined Justices Kennedy, Stevens, O’Connor, Souter, and Ginsburg in the majority opinion which ruled that a policy that permitted student-led, student-initiated prayer at high school football games violated the Establishment Clause. In his dissent, Chief Justice Rehnquist, joined by Scalia and Thomas wrote that the majority opinion “bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life” and argued that the Establishment Clause should not apply when the speech in the prayer would be that of private individuals, not the public school itself.

Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639 (2002)

Breyer issued his own dissenting opinion in the majority decided 5-4 that an Ohio school voucher program did not violate the Establishment Clause. The majority applied a newly minted Private Choice Test which found that the program (1) had a valid secular purpose; (2) the money went directly to the parents and not the schools; (3) benefited a broad class of beneficiaries; (4) was neutral about religion; and (5) there were adequate non-religious options. The majority differentiated this decision from the Lemon test because, in Lemon, the funding went straight to the schools, but in Zelman, the funding went to the parents. The dissent argued, however, that the fact that funding would go to religious instruction itself would violate the Establishment Clause.

Breyer, joined in his separate dissent by Stevens and Souter, emphasized “the risk that publicly financed voucher programs pose in terms of religiously based social conflict.” He said that although the voucher program was “well-intentioned” he did not think that “parental choice” provisions could eliminate the Establishment Clause issue. Breyer was concerned that it would not be possible for the state to treat all religions equally. He wrote, “In a society composed of many different religious creeds, I fear that this present departure from the Court’s earlier understanding risks creating a form of religiously based conflict potentially harmful to the Nation’s social fabric.”

Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005)

Breyer joined Rehnquist, Scalia, Kennedy, and Thomas in the majority opinion in this 5-4 decision that ruled that a Ten Commandments monument that had been erected in 1961 on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol did not violate the Establishment Clause because it represented historical value and not just religious value.

But Breyer did issue a separate concurrence, taking on more of an pragmatic than strictly textual approach. He described this as a “difficult borderline case” and said that none of the existing Establishment Clause tests would fit the situation. He looked at the display itself, the 40-year history, and the physical setting of the monument in a large park with 17 other monuments and 21 historical markers designed to illustrate general moral principles that the citizens of Texas had historically promoted. He then noted that there had been no sense that the monument had caused people to feel intimidated. He then stated that he believed that the Texas display was on the “permissible side of the constitutional line.” He said he would “rely less upon a literal application of any particular test than upon consideration of the basic purposes of the First Amendment’s Religion Clauses themselves. This display has stood apparently uncontested for nearly two generation. That experience helps us understand that as a practical matter of degree this display is unlikely to prove divisive.”

McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, 545 U.S. 844 (2005)

Breyer was the swing vote between the 10 commandments cases that were decided simultaneously. While Breyer found that the older Texas display was permissible because it was historical, he joined the 5-4 majority in ruling that a Ten Commandments display at a courthouse in Kentucky was not constitutional because it lacked the historical aspect present in the concurrently decided Van Orden case.

In this case, two counties in Kentucky had hung large gold-framed copies of an abridged text of the King James version of the Ten Commandments in ceremonies in 1999 in adherence to orders of the county legislative bodies that these displays be made in high traffic areas. Although the counties claimed that the display was meant to be educational, the lower courts had found that they had been displayed for a mostly religious purpose.

The Court held that the government must be neutral both between one religion and another as between religion and secularism.

Citizens United v. FEC, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

Breyer joined in Stevens’ “Concurrent / Dissent” partially agreeing with this 5-4 decision holding that the free speech clause of the First Amendment extends to corporations, labor unions, and other associations, and that attempts to limit speech constituted prior restraint. Stevens agreed that parts of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act were constitutional, but disagreed with the theory that a corporation is a person. According to Stevens, corporations were made up of individuals who did have free speech rights, but that corporations were simply collections of people without independent free speech rights.

This case formed the background for the Hobby Lobby case, in which the Court found that free exercise of religion rights extend beyond individuals to corporations and associations.

Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011)

Breyer joined Chief Justice Roberts who wrote the majority opinion in this 8-1 decision which held that people protesting on a public sidewalk about a public issue could not be held civilly liable for the tort of emotional distress even if the speech were outrageous. Members of the Westboro Baptist Church had protested at the military funeral of a Marine, Matthew Snyder, who died in the Iraq war. They posted statements on their website, denouncing how Snyder’s parents had raised him, and displayed placards with offensive comments. Snyder’s father sued for defamation, and a jury found $10.9 million in damages. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roberts stated, “What Westboro said, in the whole context of how and where it chose to say it, is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment and that protection cannot be overcome by a jury finding that the picketing was outrageous.”

Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Comm’n, 565 U.S. 171 (2012)

Breyer joined the other Supreme Court justices in ruling unanimously that federal discrimination laws do not apply to the way that religious organizations select religious leaders. Chief Justice Roberts, on behalf of the Court, wrote, “the Establishment Clause prevents the Government from appointing ministers, and the Free Exercise Clause prevents it from interfering with the freedom of religious groups to select their own.”

Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. 565 (2014)

Breyer dissented from the majority opinion in this 5-4 decision that a city may permit volunteer chaplains to open city council sessions with prayer.

Breyer wrote his own dissent, in a pragmatic manner. He emphasized the history of the case to show that the practice of holding prayers in council sessions violated the Establishment Clause. He noted that although Greece was a mostly Christian town, it also had several non-Christian congregations. Yet of more than 120 prayers between 1999 and 2010, only four had been delivered by non-Christians, and they were in 2008 after the plaintiffs in the case complained. He made some other observations about the difference between the way that Christian and non-Christian groups were treated, and cited his Van Orden approach that this was a fact-sensitive situation, and “I see no test-related substitute for the exercise of legal judgment.”

Breyer also joined Justice Kagan’s dissent, along with Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor. Kagan wrote, “When the citizens of this country approach their government, they do so only as Americans, not as members of one faith or another. And that means that even in a partly legislative body, they should not confront government-sponsored worship that divides them along religious lines.”

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. ____ (2014)

Breyer joined Ginsburg’s dissent from this 5-4 decision and also wrote his own. The majority ruled that a for-profit corporation can claim the right free exercise of religion when it ruled that closely held for-profit corporations could be exempted from federal law, that corporate owners object to, if there is a less restrictive means of furthering the law’s interest. The majority used the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) to find that the corporation had the right to be exempt from a neutral law of general applicability.

Ginsburg argued that the Court had not correctly applied RFRA, which was originally intended to restore the “compelling interest test” instead of the “least restrictive means” test. She wrote that the compelling interest test from Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963), was “a workable test for striking sensible balances between religious liberty and competing prior governmental interests.”

She then stated that RFRA applied to “a person’s exercise of religion,” and that a for-profit corporation was not a “person.” Ginsburg wrote, “the exercise of religion is characteristic of natural persons, not artificial legal entities.” She continued, citing Justice Stevens’ dissent that she had joined in Citizens United, that corporations “have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires.”

Breyer’s short one-paragraph dissent, joined by Kagan, stated that the Court should not have decided whether for-profit corporations or the owners should be able to bring cases under RFRA.

Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644 (2015)

Breyer joined the majority opinion, finding that same-sex couples have a fundamental right to marry under the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. All states were now required to perform and recognize the marriages of same-sex couples. Kennedy, on behalf of the majority, wrote, “No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.”

Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc., v. Comer, 582, U.S. ____ (2017)

Breyer joined the majority in this 7-2 decision finding that a Missouri playground resurfacing grant program that denied a grant to a religious school while providing grants to similarly situated non-religious groups violated the Free Exercise Clause. The Court found that a state could distinguish between religious and non-religious uses but not between religious and non-religious entities. The Court ruled that the State of Missouri, which had a state constitutional prohibition on aid to religious schools, had no basis for having a stronger law separating church and State than that already found within the U.S. Constitution.

Breyer wrote a separate opinion emphasizing the nature of the aid offered. He said that the state rule “would cut Trinity Lutheran off from participation in a general program designed to secure or to improve the health and safety of children.” He noted that the fact that the limits on the number of participating schools did not justify a religious distinction, “nor is there any administrative or other reason to treat church schools differently. The sole reason advanced that explains the difference is faith. And it is that last-mentioned fact that calls the Free Exercise Clause into play. We need not go further. Public benefits come in many shapes and sizes. I would leave the application of the Free Exercise Clause to other kinds of public benefits for another day.”

Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Comm’n, 584 U.S. ___ (2018)

In this 7-2 “wedding cake case” decision, Breyer joined the majority. The Court found that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission had not exercised religious neutrality when it found that baker Jack Phillips had illegally discriminated against a same-sex couple in refusing to bake a cake for their wedding ceremony.

Breyer joined Kagan’s concurring opinion that emphasized that the Colorado commission had shown hostility to religious views and not treated them with “neutral and respectful consideration.” While the state can prohibit discrimination against a protected class of people, it can only do so “if the State’s decisions are not infected by religious hostility or bias.”

American Legion v. American Humanist Assn., 588 U.S. ___ (2019)

Breyer joined the 7-2 majority in deciding that a cross on public property honoring World War I veterans did not violate the Establishment Clause. The majority found that the cross had taken on a secular meaning. This historical importance exceeded the religious symbolism.

Breyer, joined by Kagan, wrote a separate concurring opinion that once again contended that each Establishment Clause case needed to be considered on its own merits “in light of the basic purposes that the Religion Clauses were meant to serve: assuring religious liberty and tolerance for all, avoiding religiously based social conflict, and maintaining that separation of church and state that allows each to flourish in its ‘separate sphere.'” (Citing his dissent in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris.)

Breyer wrote that there was no evidence that the organizers meant to disrespect minority faiths or that it aimed to be divisive. “I agree with the Court that the Peace Cross poses no real threat to the values that the Establishment Clause serves.”

Espinoza v. Montana Dep’t of Revenue, 591 U.S. ____ (2020)

Breyer wrote a dissent from the 5-4 ruling that a Montana “no aid to religious school” rule impermissibly discriminated against religious schools and that excluding religious schools from the tax credit program violated the free exercise rights of religious schools and parents.

He again took a pragmatic approach focused on minimizing religion-based discord while securing liberty for people of all faiths. He wrote, “the majority’s approach and its conclusion, in this case, I fear, risk the kind of entanglement and conflict that the Religion Clauses are intended to prevent.”

He wrote, “We all recognize that the First Amendment prohibits discrimination against religion. At the same time, our history and federal constitutional precedent reflect a deep concern that state funding for religious teaching, by stirring fears of preference or in other ways, might fuel religious discord and division and thereby threaten religious freedom itself.”

Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru

St. James School v. Biel ( Consolidated. Decided July 8, 2020)

Breyer joined the 7-2 majority in finding that the ministerial exception prevented teachers from suing Catholic schools for age and disability discrimination. Both cases had been dismissed on summary judgment overturned by the 9th Circuit, thus bringing the issue to the Supreme Court. The Court’s 2020 decision was in line with Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC (2020) when the Court had unanimously found that people who fell under the category of “minister” were exempt from generally applicable anti-discrimination laws.

This time, Sotomayor and Ginsburg dissented, arguing that the teachers in these cases taught mainly secular subjects and did not need to be religious to teach in the schools.

Tanzin v Tanvir (2020)

Breyer joined the unanimous majority who found that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 permitted parties to sue and obtain financial damages from federal officials in their individual capacities. This decision hinged on RFRA’s meaning of the word “government,” which the Court believed included individual officials.

The case had been filed by Muslim men who had sued federal officials who they said had placed them on the “No Fly List” in retaliation for their refusal to become FBI informants against other Muslims.

This case was decided 8-0. Newly seated Justice Amy Coney Barrett was not a part of the decision.

Fulton v. Philadelphia (2021)

Breyer joined the Court in unanimously finding that the refusal of the City of Philadelphia to contract with Catholic Social Services for foster care services unless CSS agreed to certify same-sex couples violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment.

Before the decision, Court watchers thought the case could directly overturn Employment Division v. Smith (1990). But the Court found that the City failed to meet the reduced Smith standard because the Philadelphia rule was not neutral and generally applicable since it provided that the Commissioner had sole discretion to decide who was exempt from the non-discrimination standard.

Since the rule failed Smith, the Court then shifted to the compelling interest test, narrowed the issue down to the idea that while the City may have a compelling interest in enforcing non-discrimination policies, it did not have a compelling interest in denying an exception to CSS.

Breyer and Kavanaugh joined Barrett, who separately wrote that although the Court should eventually overturn Smith, the facts, in this case, did not allow the Court to do so.

Shurtleff v. Boston (Dec’d 5/2/2022)

The Court found that the city had created a public forum when it allowed groups to fly their flags from the third flagpole and that the city could not then discriminate against speakers based on their viewpoint. Boston’s program, in place for many years, had approved “hundreds of requests” for various flags ranging from flags honoring first responders to Pride flags. None were denied until 2017 when a group called Camp Constitution asked to fly a Christian flag.

In an opinion authored by the soon-to-retire Justice Breyer, the Supreme Court unanimously concluded that because it was clear the flag program conveyed the group’s views rather than the government’s views. Therefore, refusing to allow the group to raise a Christian flag discriminated based on religious viewpoint and violated the Free Speech Clause.

The majority opinion analyzed the flag request in light of history, the public’s perception of who is speaking, and the extent to which the government exercised control over speech. Justices Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch in a concurrence objected to the use of the test and said that the question should have been “whether the government is speaking instead of regulating private expression.”

The COVID-19 Cases

In late 2020 and throughout 2021, several cases were brought against state governors who had issued “emergency orders” shutting down or limiting the activities of churches.

Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo (Decided November 25, 2020)

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo had issued an order limiting worship services in “red zone” areas to 10 people, “orange zone” areas to 25 people, and “yellow zone” areas to 50% of capacity. Secular “essential” businesses had a right to operate in these areas with different restrictions. The governor reversed the worship restrictions just before the case went to the Supreme Court.

The Diocese sought a preliminary injunction to block the findings. The majority, including Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, found that the restrictions violated the “minimum requirement of neutrality” by naming religious institutions as being in a different category than “essential” businesses. They also found that the “loss of First Amendment freedoms, for even minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.” They blocked the enforcement of the restrictions.

Breyer wrote a dissenting opinion, joined by Sotomayor and Kagan, agreeing that the issue was moot because the governor had reversed the decision but arguing that elected officials had broad discretion when medical and scientific information was changing rapidly in an emergency.

Roberts dissented as Governor Cuomo had already reversed the order.

South Bay United Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, 592 U.S. ____ (February 2021)

Harvest Rock Church v. Newsom (February 2021)

The Court partially granted a church’s request for an injunction blocking California Governor Gavin Newsom’s prohibition on indoor worship services. The governor could impose a 25% capacity restriction and prohibit singing or chanting during indoor services as long as the restrictions were not discriminatory.

Breyer and Sotomayor joined Kagan’s dissent criticizing the majority’s “armchair epidemiology” and arguing that California’s regulations were neutral and treated worship just as it did secular activities with comparable COVID-19 risks, including being inside with people sitting close to each other. Since California had a “mild climate,” churches could still meet outdoors.

Between 2020 and 2021, the Supreme Court issued injunctions blocking California’s restrictions on religious worship services at least five times. These cases reached the High Court when the 9th Circuit refused to issue injunctions. The cases included Harvest Rock Church v. Newsom, South Bay Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, Gish v. Newsom, Gateway City v. Newsom, and Tandon v. Newsom.

Breyer, Kagan, and Sotomayor generally opposed the injunctions arguing that permitting religious services did not properly defer to officials’ interpretation of the rationale for the rules and that churches, and in Tandon, home worship services should have the same restrictions as secular businesses.

National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Department of Labor, Occupational and Health Admin. (OSHA), 595 U.S. ____ (January 2022)

In a 6-3 decision, the Court ruled that the Biden administration did not have Congressional authority to use the Department of Labor to establish “broad public health measures,” including mandatory vaccination or testing at companies with more than 100 employees.

Breyer joined the dissent, noting that the “temporary” OSHA mandate, scheduled to last six months, made exceptions based on religious objections and medical necessity.”

Biden v. Missouri, 595 U.S. ____ (January 2022)

Breyer joined the majority in finding that the Department of Health and Human Services could require healthcare providers that the Federal government funds via Medicare and Medicaid to require that staff be vaccinated or tested. The Court said they were held to a higher standard than other non-healthcare workers as they could contract the virus and pass it on to patients.

Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Barrett dissented, arguing that they were unconvinced that Congress gave HHS the authority to impose a vaccine mandate.

Pending Religion Cases in the Current Term

The following cases are on the docket in the current 2021-2022 term and are pending decisions. Justice Breyer is expected to participate in the rulings before his retirement at the end of the term this summer.

Carson v. Makin (Argued December 8, 2021) – Whether a state law prohibiting students from participating in a generally available student-aid program can use that aid to attend school that provide religious instruction violates the Religion Clauses or the Equal Protection Clause.

Note: Since 2016, when a Supreme Court Justice leaves the bench, we have published an objective survey of their religion clause decisions as a starting point for further inquiry. Prior Surveys have included: