When we think of Isaac Newton, we think of an apple falling, the calculus he invented to explain it, and the laws of motion that changed science forever. Newton (1642–1727) was the archetypal genius of the Scientific Revolution—a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer whose discoveries reshaped how humanity saw the universe.

But Newton was also something else: a theologian, though a quiet one. He wrote more about the Bible than about science. “I account the Scriptures of God to be the most sublime philosophy,” he declared (Richard S. Westfall, Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton, Cambridge University Press, 1980, 749). In private manuscripts, and later in his Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (1733), Newton pored over the apocalyptic visions of Daniel and Revelation. His aim was not idle curiosity. He wanted to trace the hand of God in history.

Newton’s prophetic timeline reveals as much about his faith as his formulas revealed about the cosmos. And it raises a fascinating question: how should we interpret his conclusions in light of the Adventist heritage that would emerge a century later?

Newton’s Method: A Scientist Meets Prophecy

Newton approached prophecy with the same seriousness he brought to physics. His key assumptions echoed the Protestant Reformers. He read Daniel and Revelation historically: the beasts, horns, and time periods symbolized real empires and epochs. And he adopted the day-year principle: a prophetic day represents a literal year. Thus, the “time, times, and half a time” (Daniel 7:25; Revelation 12:14), the 42 months (Revelation 13:5), and the 1260 days (Revelation 12:6) all described a 1260-year period.

“The 1260 days are years,” Newton insisted, “and consequently all those predictions… are for one and the same thing” (Observations, 25).

For Newton, the 1260 years pointed to the long reign of the papacy as the central corrupting force in Christian history. This was not a casual opinion. It was the consensus of the Reformation: Luther, Calvin, and countless others had identified the papacy as the Antichrist. Newton simply confirmed it with historical precision.

And yet, Newton was cautious. In a 1704 manuscript he warned, “It may end later, but I see no reason for its ending sooner… This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men” (Stephen D. Snobelen, “A Time and Times and the Dividing of Time: Isaac Newton, the Apocalypse, and 2060 A.D.,” Canadian Journal of History 38 [2003]: 537). He wanted prophecy to inspire faith, not frenzy.

Newton’s Proposed Timelines

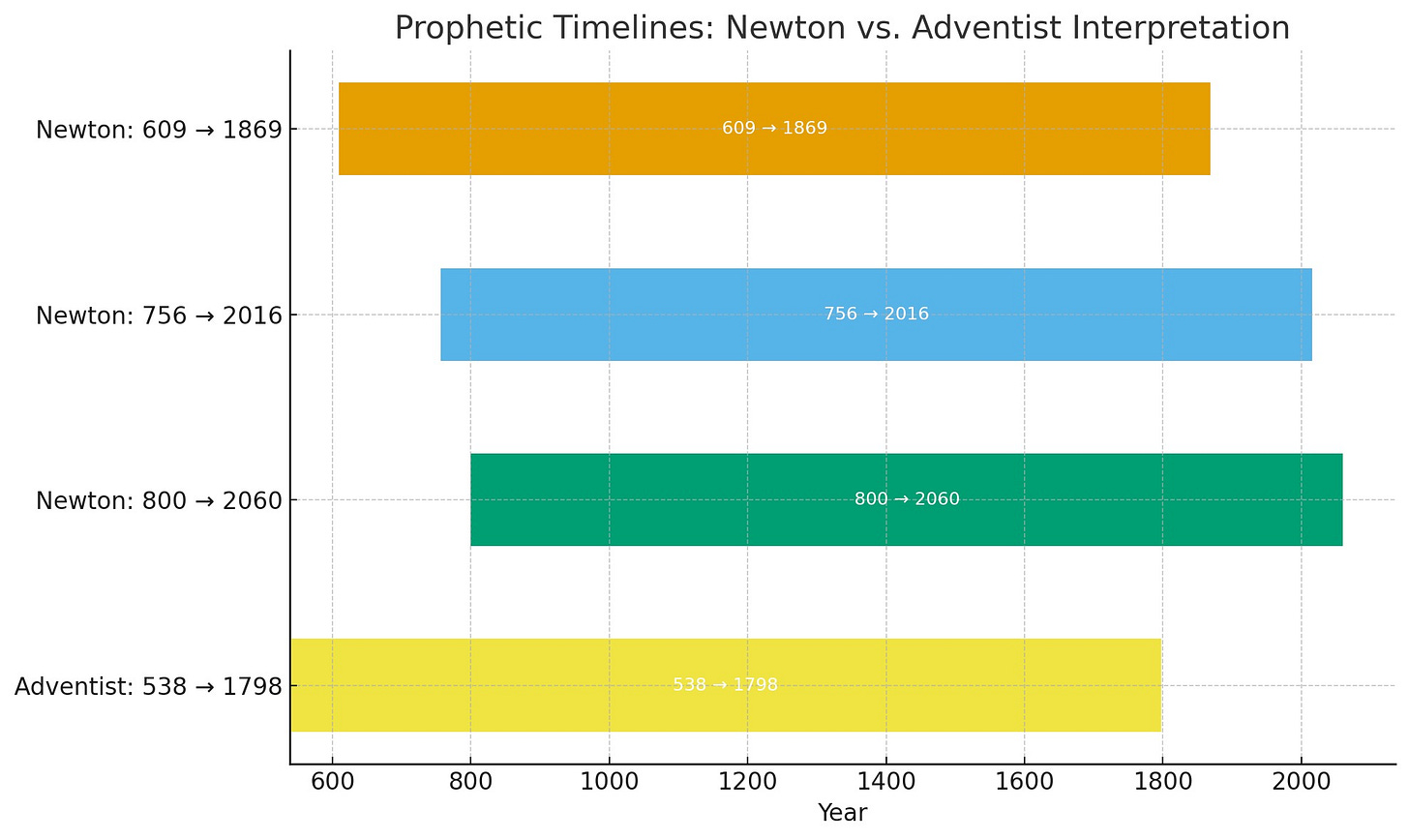

Newton explored several starting points for the 1260 years.

609 – The Pantheon Becomes a Church. In 609, Emperor Phocas gave the Pantheon in Rome to Pope Boniface IV. Newton saw this as symbolic: pagan Rome baptized into papal authority. Counting forward, the 1260 years end in 1869, the year of the First Vatican Council, when papal infallibility was declared (Frank E. Manuel, The Religion of Isaac Newton, Oxford University Press, 1974, 144).

756 – The Donation of Pepin. In 756, Pepin the Short granted land to the pope, forming the Papal States. For Newton, this was papal sovereignty made tangible. From here, the 1260 years end in 2016 (Snobelen 2003, 543).

800 – Charlemagne Crowned by the Pope. On Christmas Day, 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor. Newton interpreted this as the pope claiming authority to legitimize kings. Counting forward, the 1260 years end in 2060.

Newton became famous for that last number—not because he predicted the end would come in 2060, but because he insisted it could not come sooner. The headlines often miss his point: Newton was setting a floor, not a ceiling.

Newton on the Papacy

Newton’s identification of the papacy as the Antichrist was typical for his era. He wrote, “The King who doth according to his will, and exalts himself above every God, was the last horn of Daniel’s fourth Beast; and this King is the same with the Beast in the Apocalypse” (Observations, 55).

For him, the papacy represented a distortion of Christianity—an institution that replaced Christ’s supremacy with human authority. Yet Newton did not despise the church. He believed prophecy testified to a divine plan: corruption would last for a season, but truth would triumph.

The 538–1798 Timeline: A Protestant Consensus

Newton’s calculations were bold, but later Protestant interpreters saw the 1260 years more clearly. Many identified 538 as the beginning, when the Ostrogoths—last of the Arian kingdoms—were driven from Rome, leaving the papacy free to exercise authority. From there, the period extended to 1798, when Napoleon’s general Berthier marched into Rome, captured Pope Pius VI, and carried him into exile.

This framework—538 to 1798—became the standard among many Protestant historicists. LeRoy Froom summarized, “The very year that the 1260 years expired, the papal power received its predicted deadly wound” (The Prophetic Faith of Our Fathers, Review and Herald, 1950, vol. 2, 794).

Seventh-day Adventists later wove this interpretation into their theology, seeing it confirmed in Revelation’s “deadly wound” (Revelation 13:3) and in the unfolding of modern history. Ellen G. White’s The Great Controversy popularized it for Adventist readers.

The difference between Newton and the 538–1798 model is telling. Newton pointed forward, casting his eye into the far future. Adventists, inheriting Protestant historicism, located prophecy’s fulfillment in the near past, linking it to the sanctuary message and the three angels’ proclamations of Revelation 14.

What We Learn from Newton’s Restraint

Newton refused to indulge in exact predictions about the end of the world. That refusal is itself a lesson. Adventists share his caution: we do not set dates for Christ’s return. Jesus said plainly, “Concerning that day and hour no one knows” (Matthew 24:36).

And yet, Adventists also affirm that prophecy provides clarity. Daniel 8:14’s 2300 evenings and mornings, Revelation’s 1260 years, and the first angel’s announcement that “the hour of his judgment has come” (Revelation 14:7) point to historical realities, not abstractions. In Adventist understanding, these converged in the mid-nineteenth century with Christ’s ministry in the heavenly sanctuary.

Newton glimpsed the contours of prophetic history. Adventists believe later generations saw more of the picture. His restraint tempers our confidence; our confidence fulfills his longing. Both belong together.

Newton’s Legacy in Modern Eyes

For centuries, Newton’s prophetic papers lay scattered and unpublished. Only in 1733 did Observations appear. Much more surfaced in the twentieth century, allowing scholars to take his theology seriously.

Frank Manuel argued that “Newton did not compartmentalize his theology from his science; both were aspects of his search for God’s design” (The Religion of Isaac Newton, 1974, 98). Westfall agreed: “To see Newton whole is to see him as prophet as well as scientist” (Westfall 1980, 750).

From an Adventist perspective, this is profoundly encouraging. The greatest scientist of modernity also knelt before Scripture. His conclusions were not identical to ours, but his instincts were right: history is not random. It bends toward the reign of Christ.

Conclusion: Prophecy as Invitation

Newton’s prophetic timeline—609 to 1869, 756 to 2016, 800 to 2060—shows both brilliance and humility. He affirmed the day-year principle, identified the papacy as Antichrist, and insisted prophecy was grounded in history. His 2060 calculation, often sensationalized, was simply a guardrail against premature speculation.

Adventists affirm the same historicist method but find the clearest fulfillment in the 538–1798 period. This is not to claim monopoly on truth, but to recognize providence in history.

Reading Newton today, we should not scoff at his missteps or romanticize his genius. We should see a man who sought God with the tools he had, and who reminds us that prophecy is not about dates but about trust. The prophetic word, Peter wrote, is “a lamp shining in a dark place, until the day dawns and the morning star rises in your hearts” (2 Peter 1:19).