[dc]O[/dc]ne of the strongest examples of the power of forgiveness is found in the story, reported today by the Adventist Review, of Isaac Ndwaniye, the President of the East Central Rwandan Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. He lost his entire family to the mass genocide perpetrated by some in his own church, and yet he has gone back to serve them. If anybody ever had an excuse to abandon his calling, it is Pastor Ndwaniye.

It’s not uncommon to find church members at odds with each other over politics, but most people are content to leave those disputes outside the door of the church. One of the saddest episodes of church history occurred when Adventists were caught up in the Rwandan civil war which turned ethnic Hutus against the ethnic Tutsis. The rivalry turned into genocide in 1994. Before the fighting began, 85-90% of the people in Rwanda were Hutus and the rest were Tutsis and other ethnic minorities. When Rwanda was under Belgian control, the Tutsis were provided better jobs and better living conditions, and this disparity was a source of great frustration to the Hutus. In 1993, Belgium required all citizens to wear identification cards identifying their race, and the Hutu majority was able to identify the Tutsis and seek revenge the following year.

It’s not uncommon to find church members at odds with each other over politics, but most people are content to leave those disputes outside the door of the church. One of the saddest episodes of church history occurred when Adventists were caught up in the Rwandan civil war which turned ethnic Hutus against the ethnic Tutsis. The rivalry turned into genocide in 1994. Before the fighting began, 85-90% of the people in Rwanda were Hutus and the rest were Tutsis and other ethnic minorities. When Rwanda was under Belgian control, the Tutsis were provided better jobs and better living conditions, and this disparity was a source of great frustration to the Hutus. In 1993, Belgium required all citizens to wear identification cards identifying their race, and the Hutu majority was able to identify the Tutsis and seek revenge the following year.

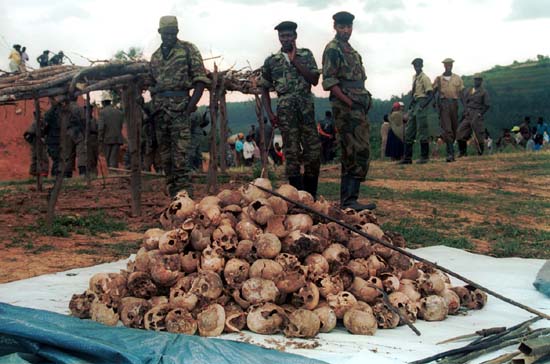

The type of physical violence associated with the Rwandan genocide is nearly unparalleled in human history, and in just over three months, 800,000 people were killed, mostly by knives, machetes, and spears and the bodies of the dead were mutilated as a large segment of the society rose up against another. Some accounts indicate there were more bodies than bullets, and one participant has since said, “Some people did not even find someone to kill because there were more killers than victims.”

He goes on to say, “It was as if we were taken over by Satan. We were taken over by Satan. When Satan is using you, you lose your mind. We were not ourselves. Beginning with me, I don’t think I was normal. You wouldn’t be normal if you start butchering people for no reason. We had been attacked by the devil. Even when I dream my body changes in a way I cannot explain. These people were my neighbours. The picture of their deaths may never leave me. Everything else I can get out of my head but that picture never leaves.”

According to the website, The Human Condition:

- Over the course of 100 days, 800,000 to 1 million Tutsis and some moderate Hutus were killed in the Rwandan genocide.

- During this period, approximately 6 men, women and children were murdered every minute of every hour of every day, which was maintained for more about 3 months.

- There are between 300,000 to 400,000 survivors of the genocide.

- Nearly 100,000 survivors are aged between 14 and 21.

- Between 250,000 and 500,000 women were raped during the 100 days of genocide, and about 20,000 children were born as a result of these rapes.

- More than 67% of women who were raped in 1994 during the genocide were infected with HIV and AIDS. In many cases, HIV+ men used rape to transfer their disease, which was a weapon of genocide.

- 7 in 10 survivors earn a monthly income of less than 5000 Rwandan Francs (Equivalent to 8 American Dollars)

- There are about 50,000 widows from the genocide.

By the time the fighting ended, one-tenth of Rwanda’s population was dead.

In 1998, Philly.com reported on the specifics of Pastor Ndwaniye’s story. Before the fighting began, a Hutu, Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, was in charge of the hospital and school compound at Mugonero. After the fighting began, 8,000 people had fled to the compound seeking safety under the impression that he could protect them because he had some influence with the local Hutus and it was a church facility. While the refugees were huddled inside the church during a worship service on a Saturday morning, on the outside, Ntakirutimana was leading a motorcade of Hutu soldiers to the compound. He stood by while they surrounded it and began to throw grenades inside. The killing continued for 11 hours and there were only a few survivors who would later testify that Ntakirutimana had supervised the killing. Both Ntakirutimana and his son, a physician, were indicted by a tribunal of crimes against humanity in 1996. Ntakirutimana fled to the United States and fought extradition. Ultimately he was convicted of genocide in 2003 and sentenced, the first clergy member to be convicted of this crime in the history of international tribunals.

The Philly describes what happened to Pastor Ndwaniye’s family.

Ndwaniye, a Tutsi, was director of publications for the church in Mugonero. He worked in the same office as [Ntakirutimana]. The rising tension in Mugonero in early 1994 was enough of a concern that when Ndwaniye was summoned to the capital, Kigali, on business on April 5, he made a point to ask the pastor to take care of his wife and nine children.

“I asked him to keep watch over my family,” said Ndwaniye, who is now director of publications at the church’s national headquarters. “I asked him that personally.”

The day after Ndwaniye left for Kigali, the genocide began. He lost his entire family at the compound.

In the Review article, Ndwaniye recounts what happened just a few months after the killing ended.

When the genocide was over in July, I traveled to Kigali and found that no Adventist church was operating in the country. So I went throughout the city, pleading with people to return to church. Slowly, people returned to the churches, and I was asked to serve as the church’s president for Rwanda for two years. Later I was elected to the publishing department of the Rwandan Union.

Five years later I was given the most challenging invitation that I have ever received: Would I be willing to serve as president of the very area that included the Mugonero compound where my family had been killed?

I prayed about it and decided to go. This would be the first time to go back and work with the people who had killed my family. I didn’t know what to say when I returned alone, so I prayed, “God help me and give me strength and words to say to these people.”

I remember spending a whole night in prayer asking God for clear direction shortly after my return. In the morning I knew that I had to call everyone together for a meeting. I knew that if I didn’t speak with the community from the very beginning, they would always feel threatened by my presence. I needed to open up my heart.

Ndwaniye was, miraculously, not bitter. He knew that some of the people who had been involved in the killing might still be attending church, and he called for a meeting.

“The Rwanda Union ‘has sent me here to preach the good news, and to lead this conference,’ I said. ‘I don’t want anyone to tell me who killed my family. I don’t even want you to tell me that you’re my friend. My friend is the one who loves God and who loves God’s work. Let’s work together in that spirit.'”

Ndwaniye says that his faith has given him the strength to continue.

“When people speak badly about the killers, I like to remind them that we have a God who is very patient with us. He’s very patient with everyone. He doesn’t want anyone to perish. That’s the only thing that can help someone like me who has gone through such circumstances. Anytime anyone comes to God and asks for forgiveness, God forgives. There’s no sin God can’t forgive. Death is not something that scares God. It’s not a big problem for God.

“Another thing that gives me strength today is knowing that my family and the other pastors and families in the compound church spent their last few days studying the Bible. They prayed to God for forgiveness of their sins and asked forgiveness from one another. That gives me strength to continue living because I know one day I will see them again. I know they are sleeping and will wake up one day. Because of that, I live for Him.”

You can read his story of at the Adventist Review website. Today, Mugonero Hospital continues as a 104-bed hospital with the mission statement, “To be instrument of God in restoring and preserving physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being of our patients and community; equally serving all: regardless of gender, age, race, religion or social status.”

###