Despite prosperity, America remains far more religious than its economic peers, echoing Alexis de Tocqueville’s 19th-century observations.

Chart from Ryan Burge – Substack

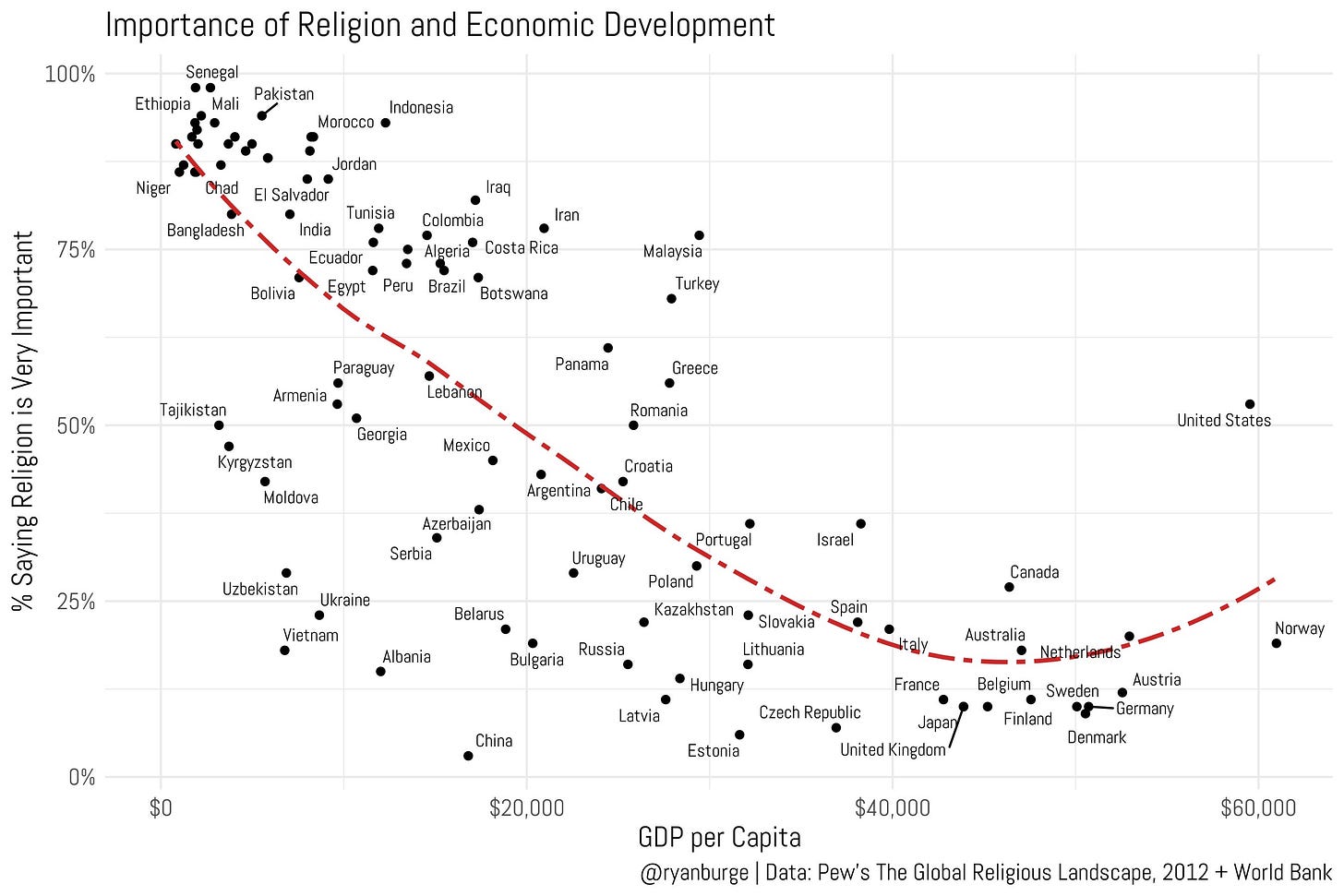

In most of the world, prosperity and secularism rise hand in hand. From Norway to Japan, economic growth tends to coincide with declining religious devotion. Yet one country disrupts the pattern: the United States. With a GDP per capita comparable to Norway, America reports that 52 percent of its population says religion is very important, compared to only 19 percent in Norway, according to Pew Research Center data compiled by political scientist Ryan Burge.

This anomaly has long been part of America’s story. In the 1830s, French thinker Alexis de Tocqueville observed that religion thrived in the United States not by controlling government, but by existing independently of it. “Religion in America… must be regarded as the first of their political institutions; for if it does not impart a taste for freedom, it facilitates the use of free institutions” (de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835). He also noted the widespread view that faith was essential to democracy itself: “I do not know whether all the Americans have a sincere faith in their religion—for who can search the human heart?—but I am certain that they hold it to be indispensable to the maintenance of republican institutions” (de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1835).

Data from Pew’s Global Religious Landscape (2012) and World Bank GDP figures, displayed in Burge’s chart, highlight the broader pattern: countries with low GDP, such as Ethiopia and Senegal, show the highest levels of religious importance, often nearing 100 percent. Wealthier countries, such as Denmark, Japan, and the United Kingdom, report much lower levels, often below 20 percent.

The United States, however, remains an outlier. While Canada, Australia, and Western European nations at similar income levels have secularized, America sustains high religiosity within a prosperous economy. One reason, as Tocqueville recognized, was the separation of church and state. In much of Europe, established churches were tied closely to monarchies or ruling powers. As political institutions weakened in the wake of revolution and modernization, state-linked churches often lost authority and public trust. The United States, by contrast, rejected a national church and instead fostered a competitive environment of denominations, sects, and voluntary associations. Freed from government patronage, American churches relied on lay support, community networks, and vibrant evangelism, which helped keep religion central to civic life even as the nation modernized.

This arrangement, Tocqueville suggested, allowed both democracy and religion to reinforce one another rather than compete. By keeping faith outside the machinery of the state, Americans ensured its resilience. That dynamic may help explain why, even in an era of prosperity, religion continues to command loyalty from large portions of the U.S. population in a way that sets it apart from other wealthy nations.

De Tocqueville’s reflections continue to resonate nearly two centuries later. The enduring religiosity of Americans, even amid economic affluence, underscores a distinctive national model: prosperity coexisting with widespread religious commitment, grounded in the very separation of church and state that he admired.

Works Cited:

de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America. Vol. 1, 1835. Translated by Henry Reeve. Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/files/815/815-h/815-h.htm.

Pew Research Center. The Global Religious Landscape. December 2012, www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/.

World Bank. “GDP per capita (current US$).” The World Bank Data, data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.