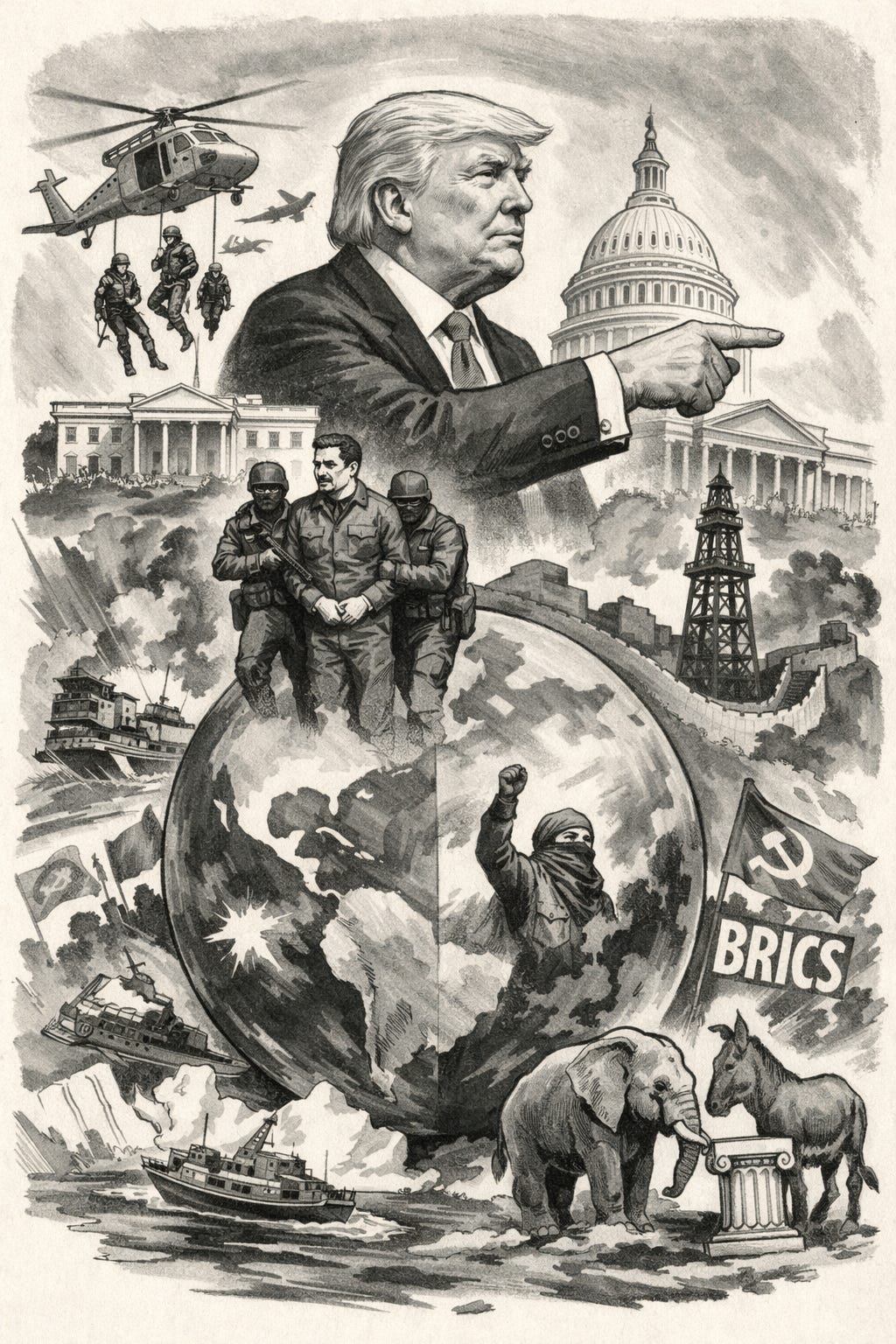

“Yeah, there is one thing. My own morality. My own mind. It’s the only thing that can stop me.” – Donald Trump, January 8, 2026.

By Michael Peabody –

The United States in 2026 is no longer arguing about policy. It is arguing about authority. The argument is no longer between left and right in any traditional sense, but between restraint and certainty, between institutional limits and moral confidence. Abroad, American power is asserted with a directness unseen in generations. At home, the political middle has thinned to the point of near extinction, squeezed from both sides by movements that no longer believe compromise is virtuous or even necessary.

At home, the political middle has thinned to the point of near extinction, squeezed from both sides by movements that no longer believe compromise is virtuous or even necessary.

This is the context in which President Donald Trump authorized the military capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, openly discussed unilateral military action inside Mexico, revived American designs on Greenland, and stated publicly that his own morality is the only real check on presidential power. It is also the context in which Democratic Socialists now govern major American cities, reshape Democratic Party priorities, and openly challenge long standing economic and constitutional assumptions.

These developments are not isolated. They are symptoms of a deeper transformation in how power is understood, justified, and exercised.

The shrinking center and the rise of certainty

The most consequential political change inside the United States is not a single election or policy. It is the collapse of the center.

For decades, American politics operated through overlapping coalitions. Republicans included libertarians, fiscal conservatives, foreign policy hawks, and social traditionalists. Democrats included labor unions, moderates, liberals, and pragmatic centrists. The system depended on tension within parties and compromise between them.

That architecture has largely dissolved.

The Republican Party that once spoke the language of limited government, congressional war powers, and skepticism of executive overreach has been overtaken by a movement that prioritizes strength, decisiveness, and loyalty to a singular leader. Small government has given way to strong government, provided it is wielded by the right hands. Executive power is no longer viewed as a danger to liberty but as the instrument through which national will is expressed.

Donald Trump does not argue for restraint. He argues for effectiveness. When he says that his own morality and his own mind are the only things that can stop him, he is not apologizing. He is articulating a philosophy. Power should be exercised by those who believe they are right.

On the other side, the Democratic Party has been pulled sharply leftward. Democratic Socialists now hold mayoral offices in cities like New York and Seattle. Their influence extends well beyond municipal governance. They shape national rhetoric on housing, policing, property rights, and economic structure. The language of reform has been replaced by the language of replacement. Capitalism is not to be managed but challenged. Markets are not to be regulated but constrained.

Moderate Democrats still exist, but they no longer set the tone. They react rather than lead. The party’s energy flows from activists who see compromise as moral failure and incrementalism as complicity.

The result is a political environment in which both parties are driven by their most ideologically confident factions. The middle ground, once crowded with swing voters and pragmatic legislators, has become a narrow strip with little institutional power.

This domestic polarization mirrors what is happening internationally.

Venezuela and the normalization of unilateral force

On January 3, 2026, United States special operations forces conducted a raid inside Venezuela and captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores. They were transported to New York and appeared in federal court on charges related to narcotics trafficking and terrorism. These indictments had existed for years. What changed was the willingness to enforce them through direct military action.

The operation was justified as law enforcement. It was not accompanied by a declaration of war. There was no regional coalition. The United Nations was not consulted. The authorization flowed from the executive branch alone.

Historically, there is precedent. The United States captured Manuel Noriega in Panama in 1989 under similar legal theories. But the Noriega operation occurred within a broader military intervention and during a different international climate. The Maduro capture took place in a world nominally governed by norms against such actions.

Inside Venezuela, the consequences are still unfolding. Vice President Delcy Rodríguez assumed interim leadership, but her legitimacy is contested. Opposition groups demand elections and political reform. Parts of the military remain divided. Oil exports have been disrupted and partially restructured under United States oversight.

What matters most is not the fate of Maduro, but the precedent established. The United States has demonstrated that it is willing to remove and prosecute a sitting foreign leader without war, without multilateral authorization, and without apology.

Other governments have noticed.

Iran and the lesson drawn from Caracas

At the same time, Iran is experiencing one of the most serious internal crises in decades. Protests that began in late 2025 over economic collapse and inflation quickly spread across the country. Demonstrators called not for reform but for the end of the Islamic Republic. The government responded with lethal force, mass arrests, and a nationwide internet shutdown.

Iranian leaders have explicitly referenced the Venezuela operation in their internal and public messaging. State media portrays it as proof that the United States is prepared to overthrow governments under the guise of law enforcement and morality. There is no evidence that the United States plans similar action in Iran. But perception drives behavior.

The result has been a hardening of repression. Security forces frame dissent as foreign sabotage. Space for negotiation has narrowed. The regime remains intact, but its legitimacy continues to erode.

This is how pressure politics spreads. One action in one country reshapes calculations in another.

Roosevelt, Japan, and pressure strategy

To understand how economic and strategic pressure can alter history, it is useful to return to 1941.

In the years leading up to Pearl Harbor, Japan expanded its empire across East Asia. The United States responded not with immediate military force, but with escalating economic pressure. First came export controls. Then came the decisive move.

On July 26, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8832, freezing Japanese government and private assets in the United States. Technically, trade was not banned. Practically, Japan was cut off from dollar based finance and from vital imports, especially oil.

Japan depended heavily on imported oil to sustain its economy and military. With reserves dwindling and no viable alternatives, Japanese leaders faced a stark choice. Retreat or seize new resources by force. They chose force, attacking Pearl Harbor and launching a wider war.

Roosevelt’s strategy was deliberate, institutional, and legally structured. It was also dangerous. Pressure applied without an acceptable exit can corner adversaries into catastrophic decisions.

In 2026, pressure is again the central tool of American strategy. The difference is that it is now applied more personally, more directly, and with less regard for multilateral process.

Greenland, Mexico, and the redefinition of sovereignty

Trump’s renewed interest in Greenland illustrates this shift. What was once dismissed as an eccentric proposal has reemerged as a strategic discussion. Greenland’s location matters for Arctic shipping, missile defense, and access to rare earth minerals. Administration officials speak openly about its value. Trump has reportedly asked for legal mechanisms to expand United States control without Danish consent.

Denmark has rejected these ideas. NATO allies express concern. But the conversation itself signals a change. Allied sovereignty is no longer treated as inviolable when it conflicts with perceived American interests.

The same logic underpins Trump’s approach to Mexico. He has publicly discussed using United States military force against drug cartels inside Mexican territory. Previous administrations also grappled with cartel violence and explored aggressive measures. The difference lies in consent.

Past efforts emphasized cooperation with Mexico. Trump speaks of acting unilaterally if necessary. Mexican officials have condemned this rhetoric as a violation of sovereignty. Yet the possibility remains on the table.

Once again, the pattern is clear. Executive decision replaces negotiated agreement.

BRICS and the fractured alternative

As the United States expands its use of sanctions, seizures, and unilateral enforcement, other nations seek insulation. The BRICS bloc, consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and newer participants including Iran and Saudi Arabia, has accelerated efforts to build alternatives to dollar dominated systems.

They discuss new reserve currencies, payment mechanisms outside traditional Western networks, and expanded commodity trade arrangements. Progress has been uneven. China and India remain rivals. Brazil and South Africa face domestic instability. Coordination is slow.

Still, BRICS matters. It offers sanctioned states options. It complicates enforcement. It signals that the global financial system is fragmenting under pressure.

Pressure creates resistance. Resistance generates alternative structures. None are fully coherent yet, but they are forming.

Law, morality, and the presidency

At the heart of all this lies a constitutional question. When a president declares that his morality is the only real check on his power, the structure of governance changes. Law becomes secondary. Institutions become advisory.

Historically, American presidents expanded power during crises, but they did so while affirming the legitimacy of constraints. Lincoln invoked necessity but deferred to Congress. Roosevelt stretched authority but respected institutional process. Even when they pushed boundaries, they acknowledged them.

In 2026, that acknowledgment is fading. Power is claimed openly and justified afterward. This is not a coup. It is a confession.

The danger is not a single illegal act. It is a pattern of governance in which legality follows will, not the other way around.

Living inside uncertainty

For individuals, these shifts are not abstract. They affect inflation, energy prices, employment, surveillance, and civil liberties. In a world governed by pressure, stability is no longer assumed.

Preparation does not mean panic. It means awareness.

Diversifying income and savings reduces vulnerability to shocks. Maintaining reserves of essential goods buffers supply disruptions. Understanding executive authority and emergency powers clarifies personal risk. Building local networks strengthens resilience. Seeking information from diverse sources guards against manipulation.

These are not ideological acts. They are practical ones.

The wager of 2026

The United States is making a wager. That power exercised decisively, guided by moral certainty rather than procedural restraint, will produce order rather than chaos. That allies will adapt. That adversaries will submit. That citizens will accept the trade.

History offers mixed evidence.

Roosevelt’s pressure helped defeat imperial aggression but led to global war. Pressure works, but it reshapes the world in unpredictable ways.

In 2026, the center has collapsed. Extremes dominate both parties. Abroad, pressure replaces persuasion. At home, authority consolidates.

This is not the end of democracy. But it is a transformation of it.

The question now is not whether power will be exercised, but whether anyone left in the system still believes it should be restrained.