Note: After I posted about the differences between the Kirk Cameron and Ray Comfort’s beliefs about hell, an alert reader contacted me and asked if I had the specific quotations from Plato that undergirded the traditional (and I would argue extra-Biblical) view of eternal torment. I realized that this is something that a lot of people probably would simply accept but others require receipts, so here are the receipts. These are long quotations and I’ve included photos of excerpts from Plato’s writings with links to the originals so you can read them for yourself. I would also advise that this is not a writing about the “State of the Dead” or what happens when you die but rather focuses on the idea of torment in hell. I welcome dialogue on this point. – MP

Christian teaching on hell is often presented as settled, biblical, and apostolic. Eternal conscious torment is preached as though it were the unavoidable conclusion of Scripture itself. Yet history tells a different story. The image of an endlessly burning hell populated by immortal souls owes far more to Greek philosophy, especially Plato, than to the Hebrew Scriptures or the earliest Christian proclamation. This is not a denial of judgment. It is an examination of origins.

Plato lived in Athens from approximately 428 or 427 BCE until 348 or 347 BCE. These dates are reconstructed from later ancient sources rather than contemporary records. He wrote centuries before Christianity existed. His world was pagan, philosophical, and shaped by myth as a moral teaching tool. Even so, his ideas would later exert enormous influence over Christian theology.

Plato wrote in dialogues, not treatises. His works present philosophical inquiry through conversation, argument, and narrative. Socrates appears as the central figure in most dialogues. Plato rarely claims certainty. He tests ideas. When argument reaches its limit, Plato turns to myth. This pattern appears most clearly in his accounts of the afterlife.

Plato was already famous during his lifetime. He founded the Academy in Athens, an institution that endured for centuries. Students traveled from across the Greek world to study there. Aristotle remained at the Academy for roughly twenty years. After Plato’s death, his writings were preserved, taught, and treated as authoritative throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods. By the time Christianity spread among Greek speakers, Platonic ideas about the soul were part of elite common sense.

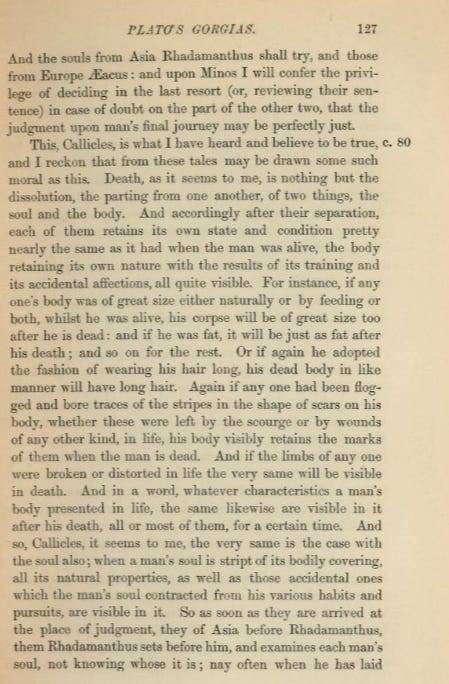

Plato made several moves that proved decisive. He treated the soul as separable from the body. He treated it as naturally immortal. He subjected it to post-mortem judgment. He divided souls into those capable of reform and those beyond it. He described punishment after death that never ends.

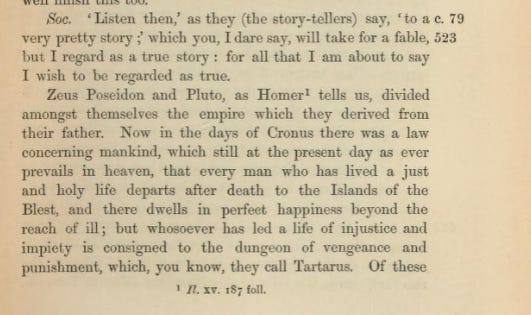

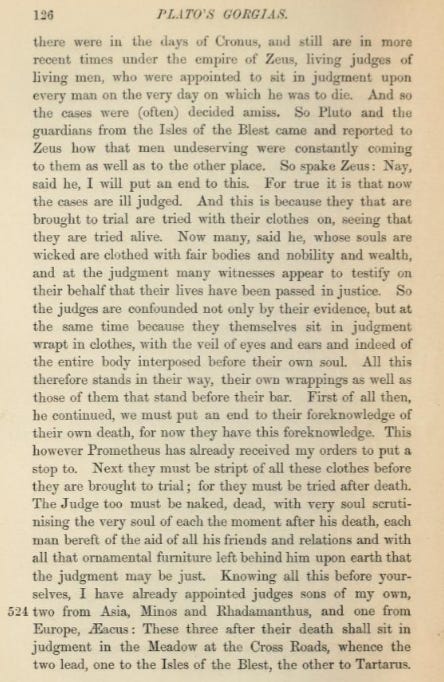

The clearest statement appears in Gorgias. Socrates recounts a myth of judgment in which souls are stripped of earthly status and examined for justice.

https://archive.org/details/platosgorgias00plat/page/124/

“Those who are judged to be incurable, by reason of the greatness of their crimes, are made examples; they are hung up in prison in the underworld, in Tartarus, as a spectacle and a warning… These men are punished for all time, and are never released.”

(Gorgias 525c–526e)

Full text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1672/1672-h/1672-h.htm

This is eternal punishment. It is not corrective. It is not temporary. Plato presents it as moral warning rather than demonstrated reality, yet the structure is unmistakable.

In Phaedo, Plato returns to the same division. Some souls suffer and are released. Others are not.

“But those who appear to be incurable, because of the greatness of their crimes… are hurled into Tartarus and never come out.”

(Phaedo 113e–114a)

Full text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1658/1658-h/1658-h.htm

Again, the emphasis rests on permanence. The soul continues. Punishment has no terminus.

In Republic Book X, the Myth of Er presents a cosmic cycle of judgment and rebirth. Most souls undergo punishment or reward for a thousand years. A small group does not return.

“And some of those who went down were never seen to come up again.”

(Republic 615e–616a)

Full text: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1497/1497-h/1497-h.htm

Plato’s universe allows eternal exclusion. His moral cosmos includes souls fixed in ruin.

These ideas did not emerge from Hebrew Scripture. The Old Testament speaks of death, the grave, Sheol. It does not teach the soul’s natural immortality. It does not describe endless conscious torment. Judgment is real. Punishment is real. Endless torture is not developed.

The New Testament uses severe language. Fire. Darkness. Destruction. It uses the term aionios, often translated “eternal.” Whether this word refers to endless duration or irreversible finality remains debated. What is absent is a philosophical argument for immortal souls suffering forever.

Christianity entered a pagan world already saturated with afterlife myths. Homer had Hades. Hesiod had Tartarus. Mystery cults promised purification beyond death. Platonic philosophy gave these myths moral coherence. When Christianity spread among Gentiles, converts brought these assumptions with them.

One assumption proved decisive. The soul was assumed to be immortal by nature. That idea came from Greek philosophy, not the Hebrew Bible. Once accepted, it reshaped everything. If souls cannot die, judgment cannot end in death. Punishment must be endless. Fire must never consume. Destruction must preserve.

Early Christian thinkers engaged this philosophical inheritance openly. Justin Martyr praised Plato for approaching truth. Clement of Alexandria treated Greek philosophy as preparatory instruction. Origen integrated Platonic categories deeply, sometimes controversially. Augustine later fused Platonic immaterialism with biblical judgment more thoroughly than any earlier figure. From that synthesis emerged the dominant Western doctrine of hell.

This process did not involve the adoption of pagan gods. It involved the adoption of pagan metaphysics. Pagan myths did not enter the Church under their own names. They entered translated into Christian vocabulary.

Tartarus became hell. The immortal soul became Christian anthropology. Mythic punishment became divine decree. What had once been allegory hardened into dogma.

This does not mean Christianity is false. It means Christian theology developed in history. It absorbed ideas. It interpreted Scripture through philosophical lenses. Some of those lenses clarified. Others distorted.

The doctrine of eternal conscious torment reflects this inheritance. It reads biblical language through Platonic assumptions. It presumes the soul cannot cease. It presumes punishment must therefore never end. It resembles Greek moral cosmology more closely than Hebrew eschatology.

Plato did not write Christian theology. He wrote pagan philosophy. Yet his shadow falls long across the Church.

If the doctrine of hell rests on Scripture alone, it should stand without Plato. If it collapses without him, honesty requires admission.

Christianity claims allegiance to truth rather than tradition. That claim invites examination.

The fire that burns forever did not begin in the Bible. It was lit in Athens.

See companion article: