TLDR (Too Long / Didn’t Read Summary)

Charlie Kirk’s posthumous bestseller, Stop, in the Name of God: Why Honoring the Sabbath Will Transform Your Life, urges Christians to keep a Friday to Saturday Sabbath as a way to unplug from technology, reduce anxiety, and recover family and spiritual life. Judith Shulevitz’s Atlantic essay, “There Were Two Charlie Kirks” (link), reads the book as a serious, if conflicted, defense of Sabbatarian theology that mixes spiritual depth with sharp right wing polemic. Seventh day Adventists, who have practiced a seventh day Sabbath for generations, welcome renewed attention to the topic but measure Kirk’s project against their own belief that the Sabbath is a creation memorial, a sign of redemption and sanctification, and a future test of loyalty. Some Adventists see his book as an opening, others as too entangled with Christian nationalism. Across these conversations, a common point emerges: Adventists do not have a monopoly on the Sabbath, and interest in weekly rest is likely to keep spreading far beyond any one group.

Charlie Kirk’s last book is quiet in subject, even if it comes from a loud career. Stop, in the Name of God: Why Honoring the Sabbath Will Transform Your Life appeared on December 9, 2025, a few months after his assassination at an event in Utah. It quickly shot to the top of online sales charts and briefly sold out, which is unusual for a modern book about a weekly day of rest.

In the book, Kirk tells a story that begins in 2021, when New York pastor David Engelhardt warned him that he was burning out under the strain of constant travel, fundraising, and broadcasting. At Engelhardt’s urging, Kirk began to keep a 24 hour Sabbath from Friday sunset to Saturday sunset. He turned off his phone, stepped away from news and social media, and devoted that time to worship, rest, and family.

Judith Shulevitz, a contributing writer at The Atlantic and author of The Sabbath World: Glimpses of a Different Order of Time (book page), picks up this story in her December 22, 2025 essay, “There Were Two Charlie Kirks” (Atlantic link). She notes that Kirk’s final work is “a book about the Sabbath,” which now joins a small shelf of serious books on rest and time while also becoming a commercial success.

In her piece, Shulevitz says the book has “moments of seriousness, beauty, and cross partisan appeal,” but also describes it as “often divisive and rarely humble.” She points readers to two Charlies at work. One is the familiar activist who attacks liberal causes with force. The other is a man who writes about his limits, and about a weekly practice that reminds him he is not God and cannot carry the world on his shoulders.

Kirk’s Sabbath: spiritual reset with a political edge

In the article, Shulevitz defines Sabbatarianism as “the doctrine of the Sabbath, the day of the week when, according to the Bible, humankind is commanded to rest.” She notes that Kirk presents his book as a defense of this doctrine. He argues that the Fourth Commandment is still relevant, that Jesus is “Lord of the Sabbath,” and that Christians should recover Sabbath practice in order to heal modern life.

Kirk describes his own practice in concrete terms. From Friday sundown to Saturday sundown he keeps his phone off, shuts down social media, avoids political content, and centers his time on prayer, Scripture reading, and long meals with family and friends. He draws inspiration from Jewish Shabbat timing and table customs, while explaining the practice in evangelical Christian language.

He calls the Sabbath a “weekly, embodied confession that we are created, not accidental,” and describes it as something that interrupts dopamine driven habits and “rehumanizes us in a dehumanizing world.” In his view, Sabbath tells people that they are more than what they produce and more than what their feeds demand from them.

The book also contains clear political themes. Kirk calls Sabbath “a political act,” a weekly declaration that his loyalty does not belong to “empire” or “the machine,” and speaks warmly of historic Sunday blue laws in the United States. He invites readers to imagine what would happen to America if commerce slowed every seventh day, screens dimmed, and attention shifted from consumption to presence and prayer.

Yet Kirk remains hesitant to say the Sabbath is binding in a strict way. He lays out reasons why Christians should honor a seventh day Sabbath, then follows with reasons that the Sabbath does not bind New Testament believers in the same way as ancient Israel. By the end, he writes that the specific day may not be the main issue, even though he himself keeps Saturday from sunset to sunset. His Sabbath is serious, but still framed as a conviction and an invitation rather than a hard line that marks who is inside or outside the faith.

Shulevitz’s Sabbath: structure and dignity in time

Judith Shulevitz approaches Sabbath with a different set of tools. She is a secular Jew, a long time journalist, and a critic of how modern societies use time. In The Sabbath World she describes the Sabbath as “a different order of time,” something that cuts across the calendar of work and consumption and forces people to stop. She argues that this kind of time, set aside every seventh day, protects human beings from becoming mere units of labor and spending.

In her Atlantic essay, she draws a line between historic sabbaths and modern “tech sabbaths.” She recalls how blue laws once made Sunday rest part of American civil life and how that pattern dissolved into weekends filled with shopping and sports. She notes that “old fashioned Sabbaths” still exist among Amish communities on Sundays and among “Seventh Day churches, such as the Adventists,” on Saturdays.

For Shulevitz, the Sabbath carries a strong claim about equality. The biblical command gives everyone, including servants and strangers, a right not to work one day in seven. That claim continues to matter wherever hourly workers and caregivers struggle to find any time that is not at the disposal of employers, customers, and screens. She is especially interested in how Sabbath limits economic activity and slows down “time deepening,” where people try to pack more into every hour and end up feeling that there is never enough time.

Reading Kirk’s book through that lens, she sees real value in his attack on digital habits. She notes that technology exerts a kind of “tyrannical” pull on attention and that a weekly phone free block of time makes sense even for those who do not share Kirk’s politics or theology. At the same time, she points out gaps in his handling of Christian argument and criticizes passages that sweep together “atheism,” anti racism, and climate activism as false religions.

Her Sabbath remains mainly a social and psychological tool, a practice that began in religious law but still offers benefits for people who no longer see themselves as observant.

Seventh day Adventists: Sabbath as gift, law, and future sign

Seventh day Adventists step into this conversation from a different direction. The North American Division’s formal statement of belief number 20 describes the Sabbath in this way:

“The beneficent Creator, after the six days of Creation, rested on the seventh day and instituted the Sabbath for all people as a memorial of Creation. The fourth commandment of God’s unchangeable law requires the observance of this seventh day Sabbath as the day of rest, worship, and ministry in harmony with the teaching and practice of Jesus, the Lord of the Sabbath.”

The same statement goes on to say that the Sabbath is “a day of delightful communion with God and one another,” “a symbol of our redemption in Christ, a sign of our sanctification, a token of our allegiance, and a foretaste of our eternal future,” and that believers “joyfully observe this holy time from evening to evening, sunset to sunset” as a celebration of God’s creative and redemptive acts. You can read the full wording at the North American Division site here: https://www.nadadventist.org/beliefs.

In daily life, Adventist Sabbath keeping looks familiar to anyone who has read Kirk or Shulevitz. Families prepare on Friday so that cooking and errands do not crowd Saturday. Members gather for Sabbath School and worship on Saturday morning, linger over meals, take walks, visit the sick or lonely, and avoid regular business activity. Adventist hospitals and schools often structure staffing and schedules so that Saturday is protected where possible. An accessible overview of this practice appears at https://www.askanadventistfriend.com/adventist-beliefs/sabbath.

Alongside that weekly rhythm, Adventist teaching links the Sabbath to future events. Material explaining belief 20 in the Inter American Division compares the Sabbath to the tree in Eden as a test of loyalty, and connects it to Revelation’s picture of a final conflict over worship. It points to Revelation 14, which describes a group who “keep the commandments of God and the faith of Jesus,” and says that Sabbath will continue to matter “down to the end of time.” That explanation can be read at https://www.interamerica.org/2022/07/belief-20-the-sabbath.

Ellen G. White, a key historical voice for Adventists, wrote in a devotional titled “The Sabbath a Test” that the Sabbath is a “sign” that marks those who belong to the Lord. That page is available at https://whiteestate.org/devotional/hb/06_02.

For Adventists, then, the seventh day Sabbath is both a weekly delight and a serious command. It is a gift of rest and community, and at the same time a visible expression of allegiance to God that they expect will become a central issue in the future.

How Adventists are reading Kirk

Kirk’s book has landed directly in Adventist discourse, and responses reveal how often Adventists interpret it through their own beliefs.

In an Adventist Review article, “Charlie Kirk’s Stop, in the Name of God,” reviewer Joe Reeves notes that the book will “help many people learn about the Sabbath and the Seventh day Adventist Church for the first time,” and that Kirk writes with real conviction about how keeping Sabbath changed his life. At the same time, Reeves describes the theology as “intertwined with social theory and partisan politics,” and observes that Kirk presents the Sabbath as “both imperative and optional” when he argues strongly for Saturday yet concludes that the exact day is not the main thing. That review can be read at https://adventistreview.org/lifestyle/charlie-kirks-stop-in-the-name-of-god.

An Adventist Today commentary by Tyler Kraft, “The Problematic Allure of Popular Validation,” addresses Adventist enthusiasm for Kirk’s Sabbath turn more directly. Kraft warns against treating celebrity interest as proof that Adventist teaching is correct, and writes that “the Sabbath does not become more valid because Charlie Kirk observed it.” He urges readers to let the Sabbath “stand on its own merit” rather than seeking “borrowed glory” from political figures. That piece is at https://atoday.org/the-problematic-allure-of-popular-validation.

Spectrum Magazine’s editor, Alexander Carpenter, adds another angle in “On Political Labels and Charlie Kirk’s Sabbath,” where he argues that Kirk’s practice sits only loosely within biblical and early Christian patterns and raises concerns that Adventist promotion of his book could blur boundaries between Adventist Sabbatarianism and Christian nationalist projects. His note appears at https://spectrummagazine.org/views/on-political-labels-and-charlie-kirks-sabbath.

Social media reactions, collected by Adventist oriented outlets, show a wide range of lay responses. Some Adventists express gratitude that a prominent conservative kept a seventh day Sabbath “sunset to sunset” and mentioned Adventists in respectful ways. Others question why the church would amplify the work of someone whose political record they see as harmful.

In short, many Adventists evaluate Kirk’s book by asking three questions.

First, how far does his practice and reasoning match or depart from Adventist belief.

Second, does his use of Sabbath language tie the day to Christian nationalist or “save America” projects that Adventists have historically resisted.

Third, are Adventists seeking validation from a controversial figure instead of trusting Scripture and conscience.

Who “owns” the Sabbath, and what the law actually cares about

Behind all of this sits a broader question that matters for religious liberty. Who, if anyone, owns the Sabbath in public conversation.

Historically, Sabbath practice began in Jewish law and life. Later, various Christian groups developed strict Sunday observance. Seventh day Adventists and a few other churches have kept Saturday as a holy day for generations. More recently, secular and mixed belief communities have adopted “tech Sabbaths” and screen free weekends as wellness practices. None of these groups has a legal or moral trademark on the word “Sabbath.”

Modern law does not ask which theology of Sabbath is correct. When a case reaches a court or a commission, the key questions are whether a person’s belief is sincere and whether a rule or policy burdens that belief. That is as true for a Seventh day Adventist nurse who wants Saturdays off, as it is for a Jewish employee who keeps Shabbat, or a Christian who starts keeping Sabbath after reading Kirk’s or Shulevitz’s work.

This is one reason some Adventists are uneasy when Sabbath becomes part of a project to “save America.” Adventists have a long record of opposing Sunday laws and other attempts to use state power to enforce religious timekeeping. When a book speaks warmly of blue laws and presents Sabbath as part of a national restoration plan, they hear echoes of past efforts to write a particular religious rhythm into civil law. Their concern is not that others are talking about Sabbath, but that civil regulation might follow.

The healthier pattern, both legally and spiritually, is for each community to teach its own convictions about Sabbath while respecting the freedom of others to come to different conclusions. Adventists can say confidently that, in their view, the seventh day still matters as a creation memorial and a sign of loyalty. Jews can continue to guard Shabbat as covenant time. Evangelicals and others can explore Sabbath as a discipline that pushes back against digital overload. Secular readers can experiment with phone free days. Courts and agencies can do their work by protecting space for those choices without picking a side in the theological debates.

Three approaches, one growing conversation

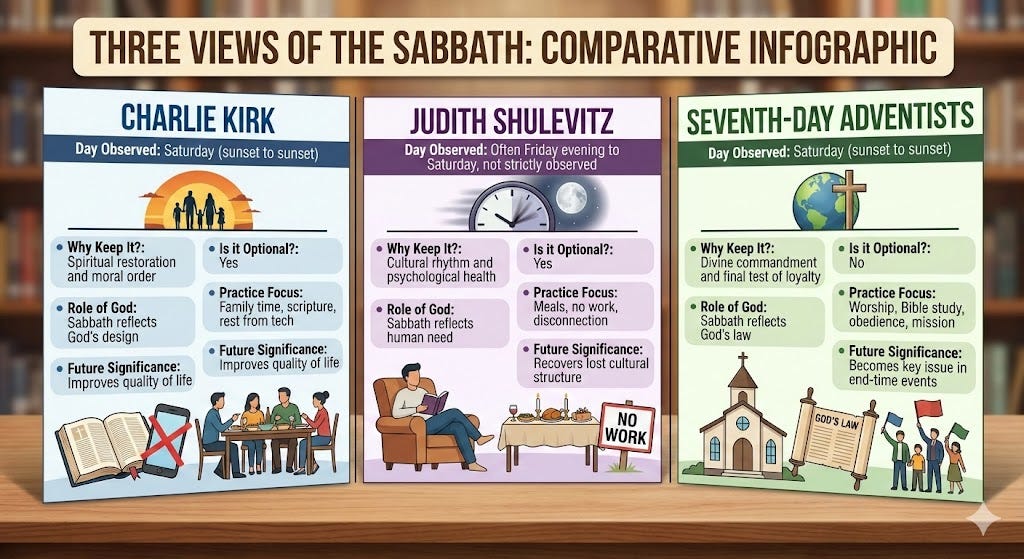

Placed side by side, the three approaches in this story answer similar questions in different ways.

What is wrong with the way we use time.

Kirk points to an overworked, hyper connected society where people never put their phones down. Shulevitz points to economies and cultures that demand constant availability and measure worth in output. Adventists point to a broken relationship with the Creator who set a pattern of six and one at the start of Genesis.

Who has authority over our calendars.

Kirk speaks of a personal God who built Sabbath into creation and invites believers to accept that gift. Shulevitz highlights the power of community agreements and inherited rituals that can still shape time even when belief has faded. Adventists point directly to the Ten Commandments and to the life of Jesus as Lord of the Sabbath.

How far should Sabbath reach into law and policy.

Kirk supports historical blue laws and calls for a broad social recovery of Sabbath, which comes close to a national program. Shulevitz is more interested in voluntary practice and informal norms. Adventists insist on voluntary Sabbath observance for all and resist civil enforcement, even while teaching their members that Sabbath is binding as a matter of faith.

Across all three, a shared insight comes through. A weekly day of rest puts a ceiling on what work, commerce, and devices can demand. It protects some time from bosses, advertisers, and algorithms. That claim has religious, social, and legal consequences, and the Kirk book has helped push those questions into a wider audience.

As interest in Sabbath continues to grow, Adventists will remain important participants in the discussion, but they will not be the only ones. Jews, secular critics, evangelical pastors, conservative activists, and ordinary readers who discover Sabbath through Judith Shulevitz’s article or Charlie Kirk’s book will keep bringing new stories and motives into the mix. Religious liberty work in the coming years will need to protect that diversity while making sure that no single version of Sabbath is written into public law.

If you found this analysis helpful, please share it and consider subscribing to ReligiousLiberty.TV on Substack at

Subscribers receive breaking news on religious liberty, detailed coverage of Sabbath and conscience cases, and plain language explanations of court decisions that affect people of faith.

AI Disclaimer:

This article was drafted with the assistance of artificial intelligence and then reviewed and edited by a human for accuracy, tone, and clarity. It relies on publicly available sources that are linked in the text.

Legal Disclaimer:

This content is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Readers should consult a licensed attorney about how any legal principles discussed here may apply to their particular situations.