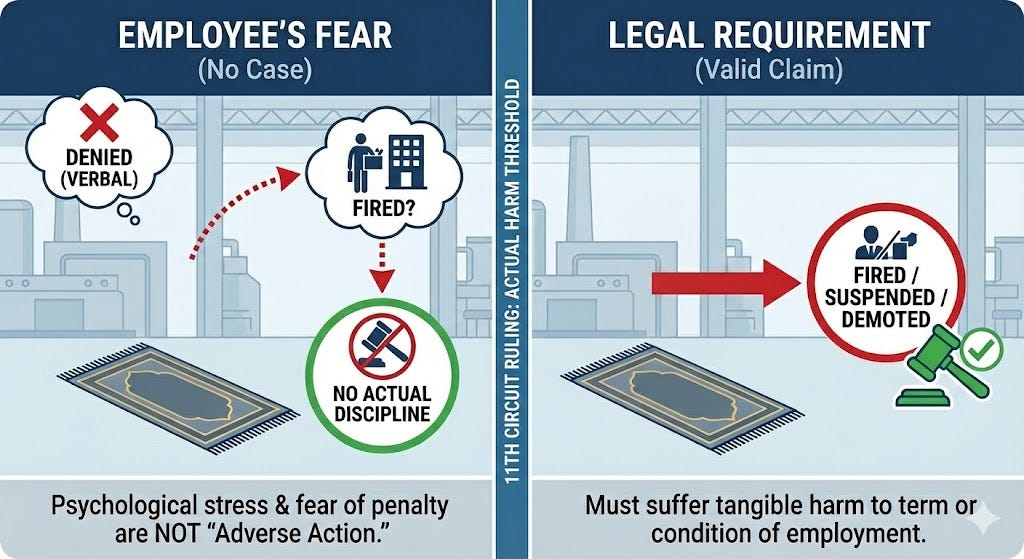

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that an employee cannot sue for religious discrimination if they never faced actual discipline. Mouatasem Zienni, a Muslim assembly line worker at Mercedes-Benz, was told he could not take unscheduled breaks to pray. He prayed anyway and was never punished. The court held that without a firing, demotion, or formal reprimand, Zienni suffered no “adverse employment action.” Even under the Supreme Court’s new Muldrow standard—which lowered the bar for proving harm—fear of discipline or psychological stress is not enough to sustain a lawsuit. This decision clarifies that employees essentially must suffer a tangible penalty before they can claim a violation of their rights in court.

Case Caption: Mouatasem Zienni v. Mercedes-Benz U.S. International, Inc., No. 24-13932 (11th Cir. Dec. 22, 2025). Link: Read the Opinion

Can you sue your employer for denying a religious accommodation if they never actually punish you for taking it? No. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last week that an employee who continued to pray despite being told not to—and faced no discipline—suffered no “adverse employment action,” effectively dismissing his Title VII lawsuit.

This ruling is critical because it defines the limits of the Supreme Court’s recent Muldrow decision. While Muldrow made it easier to show harm in discrimination cases, the 11th Circuit clarified that you still need to prove actual harm happened. Mere fear of being fired, or the stress of conflicting instructions, does not count as a violation of federal law if the employer never pulls the trigger.

What are the facts of the Zienni v. Mercedes-Benz case?

Mouatasem Zienni worked on the assembly line at Mercedes-Benz U.S. International (MBUSI) in Alabama. As a practicing Muslim, he needed to pray five times a day at specific times determined by the position of the sun.

-

MBUSI provided scheduled breaks (lunch and two others), but these did not always align with Zienni’s required prayer times.

-

Zienni asked for accommodations to take short, unscheduled breaks to pray.

-

Supervisors gave him conflicting or hostile responses. One manager, Rolanda Davis, explicitly told him he “could not pray while the production line was running.”

-

Another supervisor, Ralph Prude, allegedly mocked him, stating the team could leave early if Zienni shouted “Allahu Akbar.”

Despite these directives and comments, Zienni continued to take his prayer breaks. The record shows he never missed a prayer. More importantly, Mercedes-Benz never disciplined him. He was never fired, suspended, demoted, or formally written up. He sued anyway, arguing that the denial of the accommodation created a risk of discipline and caused him psychological distress.

How did the court justify its ruling?

The court focused entirely on the concept of “adverse employment action.” To win a Title VII claim, a worker must show that the employer’s conduct negatively affected their job.

-

No Discipline = No Case: Since Zienni ignored the “no” and prayed anyway without consequence, the court found he suffered no tangible harm.

-

Speculation is Invalid: Zienni argued he could have been fired. The court rejected this, stating that “adverse action cannot be speculative.” You cannot sue based on what might have happened.

-

Psychological Harm is Insufficient: Zienni claimed the conflict caused him anxiety and depression. The court ruled that emotional distress alone, without a change in employment status (like a pay cut or transfer), does not meet the standard for an adverse action under Title VII.

Did the Supreme Court’s Muldrow decision help Zienni?

No. Zienni tried to rely on Muldrow v. City of St. Louis (2024), where the Supreme Court lowered the threshold for discrimination claims. Muldrow held that employees only need to show “some harm” regarding a term or condition of employment, rather than “significant” harm.

-

The 11th Circuit distinguished Zienni’s case from Muldrow. In Muldrow, the officer was transferred and lost perks (a car, prestige).

-

Zienni lost nothing. His pay, hours, and duties remained exactly the same.

-

The court emphasized that the ability to take unscheduled breaks is not an inherent “term or condition” of employment unless the denial leads to a penalty.

What does this mean for your rights at work?

This decision creates a risky “game of chicken” for employees seeking religious accommodations in the 11th Circuit (Alabama, Florida, Georgia).

-

Documentation is Key: If your boss denies a request verbally but doesn’t punish you, you may not have a claim yet.

-

The “Martyr” Requirement: The ruling implies that to have a valid lawsuit, you might actually have to break the rule and get punished. If you obey an unlawful order and stop praying, you might have a claim for constructive denial. If you disobey and get fired, you have a claim for disparate treatment.

-

Empty Threats Don’t Count: If a manager threatens you but never acts, federal courts will likely dismiss your case.

Commentary

The logic utilized by the 11th Circuit here is legally sound but practically harsh. It relies on the “no harm, no foul” principle of tort law translated into employment discrimination. The court effectively told Zienni, “You got to pray, and you kept your job. What are you complaining about?” From a strict statutory perspective, Title VII is designed to remedy tangible economic or professional injuries, not to police every insensitive comment or empty threat made by a mid-level manager.

However, this creates a perverse incentive structure. It encourages employers to verbally deny rights—hoping the employee will comply out of fear—while avoiding liability by simply not enforcing the denial. It places the entire burden of risk on the employee. Zienni had to gamble his livelihood every single day, praying with the sword of Damocles over his head. The court’s dismissal of this “risk of discipline” as speculative ignores the reality of the workplace power dynamic.

The dismissal of the derogatory comment is also instructive regarding the high bar for “Hostile Work Environment” claims. While the court did not dwell on it in the short opinion, the affirmation suggests that a single, isolated—albeit repugnant—remark is not sufficient to permeate the workplace with enough hostility to change the terms of employment. Courts consistently require a pattern of pervasive abuse, not just one bad day or one bad boss.

Ultimately, this ruling is a victory for employers who want to avoid “technical” liability. It signals that federal judges are not interested in micromanaging workplace disputes where the plaintiff suffered no loss of pay or position. For the religious employee, the message is stark: You cannot sue over hurt feelings or fear. You generally must show a scar—a firing, a suspension, or a demotion—to get a federal judge to open the courthouse door.

Citations

-

Mouatasem Zienni v. Mercedes-Benz U.S. International, Inc., No. 24-13932 (11th Cir. Dec. 22, 2025). Link

-

Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, 601 U.S. ___ (2024). Link

Like, Share, and Subscribe to ReligiousLiberty.TV to get the latest breaking news and case information. Subscribers get exclusive access to our legal analysis and document archives.

Disclaimer: This article was assisted by AI. This does not constitute legal advice. Readers are encouraged to talk to licensed attorneys about their particular situations.

Tags: Title VII, Religious Accommodation, 11th Circuit, Workplace Rights, Employment Law

Holding: An employee cannot sue for religious discrimination under Title VII without suffering an actual adverse employment action such as firing, demotion, or formal reprimand; fear of discipline or psychological stress alone is insufficient.