The 2026 U.S. operation that captured Nicolás Maduro raises old questions about law, resources, and who really controls the post-dictator future of Venezuela

Friday night, Nicolás Maduro was captured by the U.S. in January 2026. While his dictatorship lacked legitimacy, the method of removal without public legal process or international mandate raises questions about the rule of law. Venezuela’s oil industry was originally built by U.S. firms and left buried under debt. Its untapped silver reserves had begun to attract BRICS-aligned interests. Maduro’s economic pivot away from the dollar-based order may have sealed his fate. With his removal, oil, silver, and debt restructuring are once again on the table with U.S. firms poised to benefit.

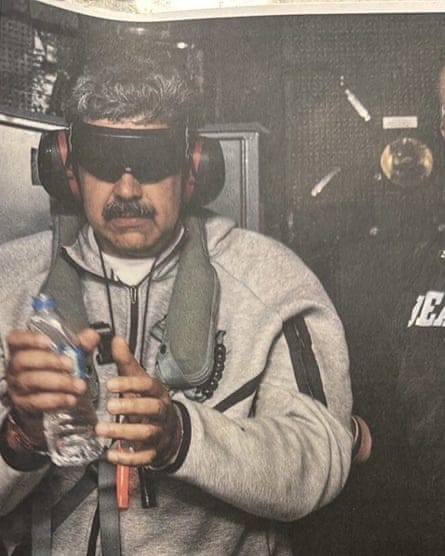

They have him. Nicolás Maduro, the last man standing from Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian project, was plucked from Venezuelan soil in a January 2026 U.S. operation that officials now openly describe as a disruption strike. He is in custody.

There is no verified successor in office. No functioning, civilian-led transition authority. No legal documentation released showing authorization from Congress. What there is, instead, is silence from the Organization of American States, watchful caution from the United Nations, and quiet alarm from the BRICS nations who, unlike Washington, had never stopped recognizing Maduro’s presidency.

This is not about whether Maduro was a dictator. He was. It is not about whether he deserved to lose power. He did. This is about what happens when the world’s most powerful nation, under the banner of justice, replaces process with precision and law with leverage.

The Oil, the Silver, and the Original Debt

Venezuela was never a poor country. It was made poor.

In the 1920s, Standard Oil helped shape the modern Venezuelan economy. American and European firms drilled the wells, built the ports, and then sent the invoices. Venezuela borrowed to build its oil sector, paid with its oil, and remained structurally dependent on foreign capital markets. This debt burden defined its politics long before Chávez arrived.

But oil was not the only extractive prize. Venezuela also holds among the world’s largest untapped reserves of silver, particularly in the Guayana Shield, a mineral-rich region in the southeast. While not as politically charged as oil, silver has taken on growing economic significance in the global metals market. Since 2022, silver demand for electronics, solar panels, and military applications has climbed steadily. Venezuela’s deposits are largely undeveloped, but Chinese and Russian interests had quietly moved in.

Maduro’s 2023 mining reform proposals, promoted under the banner of resource sovereignty, opened limited silver concessions to BRICS-aligned firms while keeping Western companies locked out. It was not just about ownership. It was about bypassing the U.S. dollar-centered trade and debt ecosystem. When oil is political, silver becomes strategic.

The same pattern emerged. Foreign firms build the infrastructure. Venezuela pays in access and loses autonomy. But now, with BRICS offering alternatives to IMF lending and dollar payments, Maduro had begun to shift silver extraction into new financial channels. That was not just business. That was exit behavior.

The Oil, the Silver, and the Original Debt

Venezuela was never a poor country. It was made poor.

In the 1920s, Standard Oil helped shape the modern Venezuelan economy. American and European firms drilled the wells, built the ports, and then sent the invoices. Venezuela borrowed to build its oil sector, paid with its oil, and remained structurally dependent on foreign capital markets. This debt burden defined its politics long before Chávez arrived.

But oil was not the only extractive prize. Venezuela also holds among the world’s largest untapped reserves of silver, particularly in the Guayana Shield, a mineral-rich region in the southeast. While not as politically charged as oil, silver has taken on growing economic significance in the global metals market. Since 2022, silver demand for electronics, solar panels, and military applications has climbed steadily. Venezuela’s deposits are largely undeveloped, but Chinese and Russian interests had quietly moved in.

Maduro’s 2023 mining reform proposals, promoted under the banner of resource sovereignty, opened limited silver concessions to BRICS-aligned firms while keeping Western companies locked out. It was not just about ownership. It was about bypassing the U.S. dollar-centered trade and debt ecosystem. When oil is political, silver becomes strategic.

The same pattern emerged. Foreign firms build the infrastructure. Venezuela pays in access and loses autonomy. But now, with BRICS offering alternatives to IMF lending and dollar payments, Maduro had begun to shift silver extraction into new financial channels. That was not just business. That was exit behavior.

PDVSA: The Ghost Company

Venezuela’s oil sector still runs through PDVSA, Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A., the national oil company created in 1976. Once a global leader, PDVSA was gutted by purges, sanctions, and incompetence. Chávez politicized it. Maduro militarized it. By 2024, PDVSA was exporting under half its 2015 output. Yet it remained central to any discussion of Venezuelan economic recovery.

PDVSA was also deeply in debt. It had borrowed heavily on international markets with oil as collateral. Citgo, its U.S.-based refining subsidiary, was frozen in court battles. Any successor government will have to renegotiate that debt. Control of PDVSA and control of mineral concessions like silver will be the real currency of whatever comes next.

BRICS and the Broken Architecture

The 2026 operation cannot be understood outside the context of financial realignment. The BRICS bloc, Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, was no longer just hosting summits. It was offering infrastructure loans, currency alternatives, and trade routes that bypassed the U.S. dollar. Venezuela, facing years of sanctions and frozen assets, had every reason to embrace BRICS.

BRICS responded in kind. Chinese firms backed mining operations in the Orinoco Belt. Russian advisors supported internal security. Indian conglomerates expressed interest in lithium, rare earths, and silver.

Maduro’s push toward BRICS threatened more than diplomatic alignment. It undermined the postwar financial order the U.S. helped build and has long enforced. If a resource-rich country could survive outside the dollar, others might follow.

Voting Machines and the Mask of Legitimacy

Maduro’s elections were rigged. That was never in dispute among international observers. Smartmatic, once the supplier of Venezuela’s election systems, publicly distanced itself after the 2017 constitutional vote and accused the regime of manipulating turnout. Domestic opposition was jailed, disqualified, or driven into exile. By 2026, there was no real electoral legitimacy left.

But this collapse of legitimacy had become useful to Washington. In a post-2020 U.S. political climate where even domestic election systems were under attack, Venezuela became the symbolic endpoint. A place where voting machines turned authoritarian and software devoured sovereignty.

Maduro’s fraud became more than a local problem. It became evidence. For some, his capture was framed as a global correction. But correcting fraud with force is not justice. It is intervention wrapped in justification.

The Doctrine of Reach

Maduro was indicted by the U.S. in 2020 on charges of narco-terrorism. Those indictments sat dormant for years. Then, in January 2026, they became the basis for a military operation with no publicly declared authorization.

International law protects sitting heads of state from unilateral arrest by foreign powers. That doctrine rests on sovereign equality. But the United States has long observed a different rule. If you are indicted and cannot fight back, you are within reach.

In 1989, Noriega was captured after a full invasion. His trial in Miami became a precedent. In 2026, Maduro was taken by special forces. No public vote. No declaration of war. No occupation. Just silence, precision, and extraction.

That may be power. It is not law.

Debt and the Future Market

Venezuela’s external debt exceeds 150 billion dollars. This includes bondholders, arbitration judgments, Chinese loans, and collateralized assets abroad. Its mineral wealth, including oil, gas, and silver, represents the only realistic source of repayment.

Now, with Maduro gone, the question becomes who signs the contracts. Will the new authority open silver mining to U.S. firms? Will Citgo be restored or sold off? Will debt be forgiven, restructured, or enforced?

The same firms that built Venezuela’s extractive economy, Chevron, Halliburton, Schlumberger, are reportedly watching events closely. Their return depends on the legal clarity of the post-Maduro order. Which is to say, their return depends on American recognition of the new regime they helped install by removing the old one.

What Now

Maduro is confirmed to be in U.S. custody.

There is no verified successor government.

PDVSA is in limbo.

Silver concessions and oil contracts are in play.

BRICS members have condemned the operation and requested emergency diplomatic consultations.

There will be calls for democracy. But the mechanics will be legal, financial, and extractive. The silver is still underground. The oil is still in the ground. The question is who gets to sign for it.

Plain Language Analysis

Maduro ruled by fraud and repression. But even bad rulers must be removed the right way. If the U.S. says it believes in law, it cannot use force without process.

This was not only about politics. It was about money. Venezuela has oil and silver. It owes billions. Its trade was shifting toward countries that do not use the U.S. dollar. That made it a threat.

Now Maduro is gone. But law did not win. Power did.

Support Our Coverage

If you value clear reporting on global legal power, debt, and resource politics, share this article and subscribe to the ReligiousLiberty.TV blog at religiouslibertytv.substack.com. Subscribers receive timely case updates, global legal analysis, and in-depth coverage of issues governments do not explain.

AI Disclaimer

This article was created with the assistance of artificial intelligence. It does not constitute legal advice. Please consult a licensed attorney for legal guidance.

SEO Tags

Maduro capture 2026, Venezuela silver reserves, PDVSA and U.S. oil, BRICS economic challenge, regime change and international law