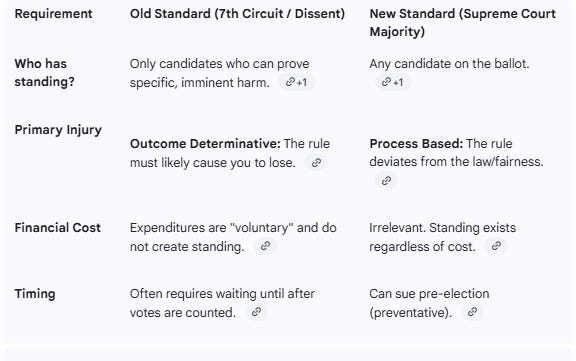

On January 14, 2026, the Supreme Court ruled in Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections that political candidates automatically have standing to challenge vote-counting rules in federal court. Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, held that candidates possess a distinct interest in the “fairness” of the electoral process that separates them from the general public. This decision reverses a Seventh Circuit ruling that dismissed Congressman Michael Bost’s lawsuit because he could not prove the challenged rule would cause him to lose his election or cost him money. Justice Barrett concurred in the judgment but argued standing should rely on financial costs incurred by campaigns. Justice Jackson dissented and argued the Court effectively removed the “injury in fact” requirement for politicians.

Case Information

Case Style: Bost et al. v. Illinois State Board of Elections et al. Case Number: No. 24-568 Date Decided: January 14, 2026 Court: Supreme Court of the United States

The Ruling

The Supreme Court ruled on Wednesday that political candidates possess automatic legal standing to challenge election administration rules. The majority held that a candidate’s interest in a “fair process” satisfies Article III requirements without the need to demonstrate financial loss or a substantial risk of defeat.

Why This Matters

This decision lowers the procedural barrier for politicians seeking to contest ballot-receipt deadlines and counting procedures in federal court. By rejecting the Seventh Circuit’s requirement that plaintiffs prove a specific probability of electoral defeat, the Court has clarified that the “personal stake” required to sue is inherent in the status of being a candidate. This distinction separates candidates from ordinary voters and allows pre-election challenges to proceed without speculative evidence regarding final vote tallies.

What are the facts of Bost v. Illinois State Board of Elections?

Illinois election law mandates that officials count mail-in ballots postmarked by Election Day even if they arrive up to two weeks later. Congressman Michael Bost filed a lawsuit arguing that counting ballots received after Election Day violates federal statutes setting the election date. Bost claimed the rule forced his campaign to spend resources monitoring late ballots and undermined public confidence.

The District Court and the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the case. The Seventh Circuit reasoned that Bost lacked standing because he won his previous election with 75% of the vote. The lower court asserted that Bost could not show the rule would change the outcome or that his financial expenditures were anything other than voluntary measures to avoid a hypothetical harm.

How did the majority define candidate standing?

Chief Justice Roberts delivered the opinion of the Court. He argued that candidates are not “mere bystanders” in elections. The Court determined that an unlawful election rule injures a candidate’s interest in a fair process. Roberts wrote that a candidate’s interest in the “prize” of office cannot be severed from the process used to award it.

The Court used the analogy of a footrace to explain the injury. Roberts noted that a runner in a 100-meter dash suffers an injury if the race is unexpectedly extended to 105 meters. This injury exists regardless of whether the runner expects to win or lose. The opinion states that requiring candidates to predict election outcomes to establish standing would turn judges into “political prognosticators”.

What was Justice Barrett’s concurring view?

Justice Barrett, joined by Justice Kagan, concurred in the judgment but rejected the majority’s reasoning. Barrett argued that Bost had standing based on a traditional “pocketbook injury”. She pointed to the specific costs the campaign incurred to hire poll watchers to monitor late-arriving ballots.

Barrett criticized the majority for creating a special standing rule based solely on candidate status. She argued that the Court should have applied standard precedents which allow standing when a plaintiff incurs costs to mitigate a “substantial risk” of harm. In her view, it is reasonable for a candidate to spend money monitoring vote counts to prevent the acceptance of invalid ballots.

Why did Justice Jackson dissent?

Justice Jackson, joined by Justice Sotomayor, filed a dissenting opinion. She argued that the majority eliminated the “injury in fact” requirement for political candidates. Jackson contended that an interest in a “fair process” is a generalized grievance shared by all voters and is insufficient for federal standing.

The dissent warned that the ruling creates a “bespoke” rule for politicians that does not apply to other litigants. Jackson argued that Bost failed to allege any actual harm because he did not show the late ballots would favor his opponent or threaten his victory. She expressed concern that the decision would encourage candidates to file disruptive lawsuits challenging minor ballot formatting issues even after losing an election in a landslide.

Analysis & Commentary

The Supreme Court has effectively carved out a specific exception to the rigorous “injury in fact” doctrine for political candidates. While the Court frames this as a recognition of the “distinct” interest candidates hold, the practical effect is the removal of the requirement to prove imminent harm. In most civil litigation, a plaintiff must show that a statute hurts them specifically—financially, physically, or reputationally. Here, the Court says the hurt is the deviation from the rules itself.

This approach aligns the judiciary more closely with the role of an election referee rather than a dispute settler. By rejecting the need for a candidate to show they might lose, the Court acknowledges the reality that election integrity is often litigated in the abstract before votes are cast. If the Court had upheld the Seventh Circuit, it would have created a paradox where a candidate could only sue if the election was close enough to be stolen.

However, the dissent raises a valid point regarding the potential for frivolous litigation. If “fairness” is the only metric required for standing, candidates may theoretically challenge trivial administrative decisions—such as font sizes or booth placements—without showing how those decisions negatively impact their specific campaign. The majority attempts to limit this by focusing on vote-counting rules, but the logic of “process as a prize” could be expansive.

Justice Barrett’s concurrence offers a narrower, perhaps more traditional, path. By focusing on the money spent on poll watchers, she attempts to ground the decision in tangible economic loss. The majority likely rejected this because it relies on the “voluntary” nature of the expenditure. If the Court adopted Barrett’s view, standing would become a pay-to-play system where well-funded campaigns that can afford poll watchers have standing, while underfunded grassroots candidates do not.

What happens next?

The judgment of the Seventh Circuit is reversed, and the case is remanded for further proceedings. The lower courts must now adjudicate the merits of Congressman Bost’s claim that the Illinois ballot-receipt deadline violates federal statutes.

Like, share, and subscribe to ReligiousLiberty.TV for breaking news and case info. Subscribers receive immediate access to detailed legal analysis and case updates.

AI Disclaimer: This article was assisted by AI. Legal Disclaimer: This does not constitute legal advice. Readers are encouraged to talk to licensed attorneys about their particular situations. Tags: Supreme Court, Bost v Illinois, Election Law, Article III Standing, Mail-In Ballots

Holding: Political candidates possess automatic legal standing to challenge election administration rules based on their interest in a fair process without needing to demonstrate financial loss or substantial risk of electoral defeat.