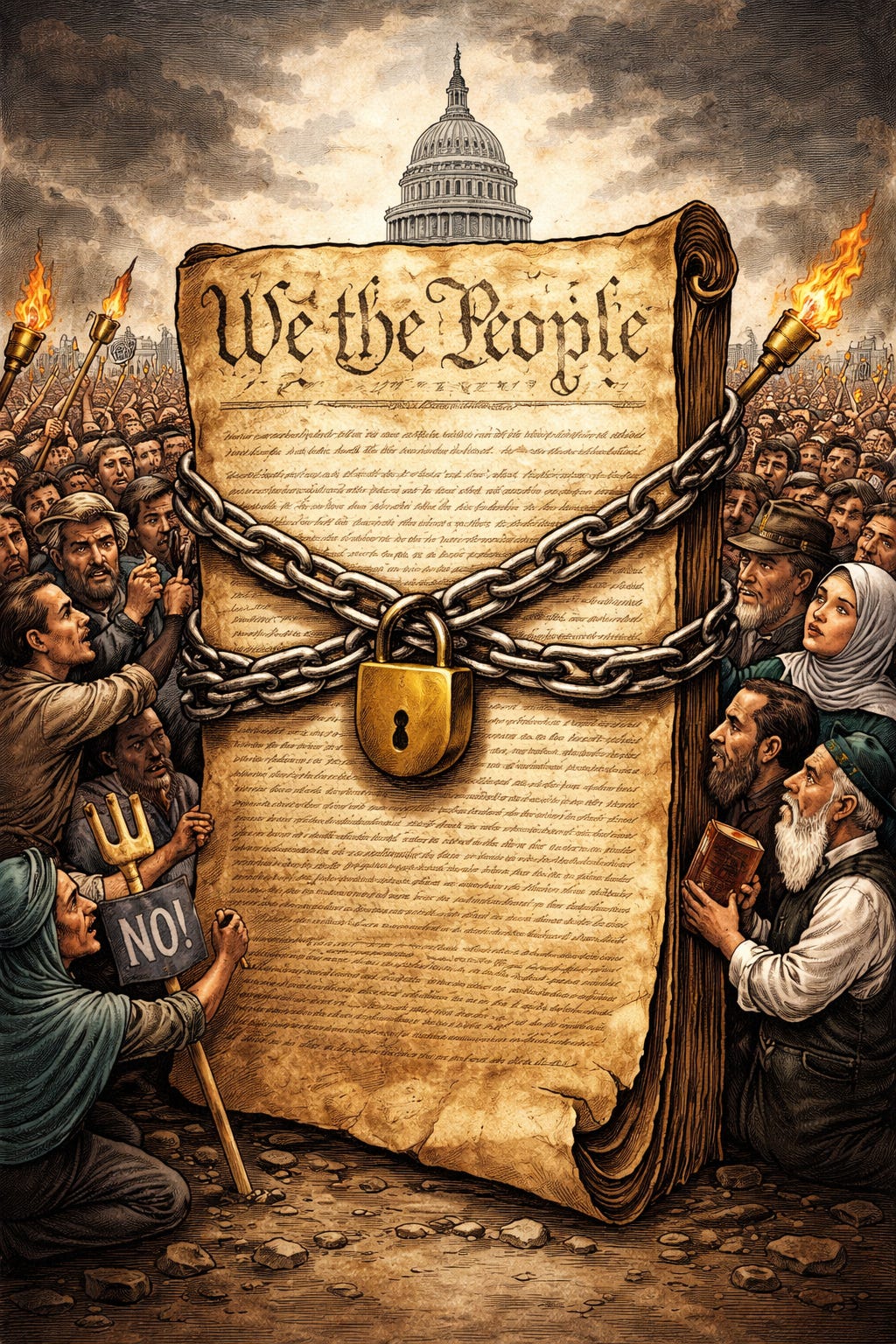

The Constitution was built to cool democratic fever, not to flatter it.

Democracy is a fine instrument until it decides you are the problem.

As the United States approaches its 250th anniversary in 2026, we are taking time to examine the constitutional architecture that has sustained the republic since 1787. This article is part of our ongoing observance of that milestone, focusing on the structural safeguards that have preserved religious liberty and restrained majority power for nearly two and a half centuries.

By Michael Peabody –

Give a majority enough confidence in its own virtue and it will regulate your conscience before lunch. It will tell you which prayers are acceptable, which symbols offend, and which beliefs are backward. It will do all this with ballots, committees, and tidy legislative findings. The paperwork will look immaculate. The liberty lost will not.

The Framers understood this. They did not construct a system that worships majority will. They built one that suspects it.

The First Amendment declares that Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. Those sixteen words do not float in isolation. They are anchored in a structure designed to frustrate sudden passions. Two houses of Congress. A presidential veto. Judicial review. Federalism. And an amendment process in Article V that requires two thirds of Congress and three fourths of the states to alter the text.

That is not procedural clutter. It is a defense system.

Religious minorities have rarely enjoyed the comfort of popular approval. Catholics in the nineteenth century faced political movements organized around their exclusion. Jewish Americans encountered formal and informal barriers. Jehovah’s Witnesses were arrested for refusing to salute the flag. Muslims and Sikhs have faced zoning fights and surveillance disputes in the modern era.

In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 1943, the Supreme Court confronted a state rule requiring public school students to salute the flag. Jehovah’s Witness students refused on religious grounds. The Court held that the state could not compel the salute. Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote, “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

That ruling did not mirror majority sentiment at the time. It restrained it.

This is the point that makes enthusiasts of unfiltered democracy uneasy. The Constitution protects you most forcefully when your views are least fashionable. It assumes that majorities can be impatient, moralistic, and certain of their own righteousness. It therefore divides power and slows lawmaking.

Consider the amendment process. If a bare majority of Congress and a slim national vote could revise the First Amendment, periods of fear or anger could narrow religious liberty with alarming speed. Article V makes that improbable. Any amendment must clear a supermajority in Congress and win ratification in three fourths of the states. That requires persuasion across regions, cultures, and political factions.

Critics call this rigidity. They argue that structural features frustrate democratic will. They are correct that the system frustrates. That is the intention. A constitution that bends with each electoral gust is not a constitution. It is a mood ring.

The concept often labeled tyranny of the majority is not abstract theory. It is the practical risk that 51 percent, convinced of its virtue, will impose orthodoxy on the rest. Religious freedom exists precisely to deny that impulse legal authority.

Federalism adds another layer of protection. States possess regulatory authority, but the Fourteenth Amendment applies the First Amendment’s protections against them. That amendment itself required overwhelming national agreement after the Civil War. It demonstrates that constitutional change can expand liberty, but only when consensus is deep and durable.

None of this guarantees perfect outcomes. Courts disagree. Legislatures test boundaries. Litigation continues. But the framework forces conflict into legal channels rather than raw political dominance.

The protection of minority rights is not sentimental charity. It is structural self interest. Majorities change. Demographics shift. The safeguard you dismiss today may defend you tomorrow.

Amendment proposals that would alter the First Amendment or related protections would need to satisfy Article V. That means two thirds of both houses of Congress and ratification by three fourths of the states. Until such thresholds are met, religious liberty remains shielded by a system designed to distrust concentrated power.

TLDR (Too Long / Didn’t Read Summary)

Majorities can pass laws that burden religious practice. The Constitution sets limits on that power. Courts enforce those limits even when the protected group lacks broad support.

The amendment process adds another safeguard. Changing constitutional text requires overwhelming agreement. That makes it hard to restrict religious liberty during moments of fear or political pressure.

If you value freedom of conscience, you should value structural limits on majority rule. The rules that protect minority faiths today may protect your beliefs in the future.

This article does not constitute legal advice. Readers should consult licensed attorneys regarding their specific circumstances.

For ongoing coverage of religious liberty and constitutional law, subscribe to ReligiousLiberty.TV at https://religiouslibertytv.substack.com. Subscribers receive breaking updates, case analysis, and detailed reporting. Please like this article, share it, and subscribe to stay informed.

Tags: Religious freedom, First Amendment, minority rights, Article V, constitutional law

Holding: States cannot compel students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance or salute the flag when doing so violates their religious beliefs.